6 de November de 2023

What is velocity based training and why do we need to do more than just traditional strength training?

Understanding Velocity Based Training – Part 1

For decades, athletes have strength trained and lifted weights in an effort to get stronger, stay “fit,” and aid their athletic performance. Over the course of time, new techniques and information have become abundant and helped shape the landscape of strength and conditioning for team-sports and athletics as a whole. One particular area that has evolved is the idea of “velocity based training,” and what it means to move weights with speed and intent. This leads me to why I am here talking to you today. What IS velocity based training and why do we need to do more than just traditional strength training when it comes to developing team-sport athletes OUTSIDE of sport?

However, before I begin to unpack this, I want to remember what my friend Bob Alejo once said, “show me something new people are doing in strength and conditioning and I will tell you what we called it 25-30 years ago.” This is an important sentiment to me. Why? Well, we cannot act as if the idea of moving a barbell as fast as possible is “new.” That is not what I am here to accomplish today. What is new, however, and IS what I am here to accomplish today is the burgeoning amount of affordable technology to help us measure the speed in which the barbell is moving!

Over the coming months I am going to walk you through an understanding of velocity based training in its entirety. What it is, why we would use it, how we would use it and several cool intricacies that can help us enhance what we are doing when it comes to our strength and conditioning and programming.

It is critical to me that I start from the beginning and give even the most novice or beginner coach the tools they need to better utilize velocity based training and get everything they can from their Vitruve encoder and the data and information it provides.

As such, let’s get right to it and start with the main essentials of velocity based training and why it is a tool we MUST have in our toolbox as strength and conditioning coaches and athletes.

Athletics: there is NOT an infinite amount of time to produce force

I want you to think about most sports. Think about a violent and powerful homerun swing from your favorite power hitter in baseball. I want you to consider how FAST an NBA player moves through the lane to throw down a ferocious dunk. What about a quarterback in American Football? Think of some of the great athletes in this new generation and how they can quickly whip a ball forty yards or sprint downfield to avoid a lineman.

Of course, think about olympic sprinters and the speed and rate in which they contact the ground per-stride to exhibit an insane amount of force. I could go on and on, but you get the point. Sports DO NOT allow an athlete an infinite amount of time to exert force in movement.

Think of a powerlifter. They can take as long as they would like to grind through a World record repetition as long as they complete it and the movement is deemed to be complete by judges.

A sprinter, thrower, quarterback, point guard or slugging first basemen live by different rules. Yes, they are extremely forceful, but they ALSO display that force in the context of extremely short and small windows of time, or else they wouldn’t be very fast or explosive.

This exact sentiment is why strength and conditioning cannot simply focus on traditional, 1-5 rep strength building exercises. This is not to say that type of training doesn’t have a place. It absolutely does and frankly, can be the foundation for almost all developing athletes and play somewhat of a role in developing elite force production that can take part in our power driven activities.

However, after an athlete has developed a base level of strength, the correlation between strength improvement/number improvement on a strength lift and things such as jump height, sprint speed or other various power based movements will begin to diminish.

This is where we must consider the difference between the context/time it takes to exert force to develop a heavy lift and the time it takes for a sprinting ground contact, extension on a jump or rotation on a throw (the list can go on and on).

Once the athlete moves past this beginner/novice level, it is imperative that they begin to explore the gray area that exists between traditional strength training and traditional, unloaded/max speed jumps and sprints. This is where velocity based training comes in!

We must work to move loads in a shorter amount of time to develop POWER

At a later date we will touch on the force-velocity curve and discuss the basic rundown of the sliding spectrum that exists between various loads, speeds and types of movements.

For now, I want to hammer the basic idea that there must be a part of our training that exists to move varying loads at varying speeds outside of the traditional aspects of strength or unloaded speed and jump training.

Simply put, power is the idea of:

Speed x force

Keep it simple… How much force can we produce in a given amount of time?

More force produced in a similar amount of time = improved power

Similar amounts of force produced in a shorter amount of time = improved power as well

This is the essence of dynamic-effort lifting, various loading applied to sprints and jumps and the overall idea of velocity based training. For now, velocity based training is our main focus.

You notice I mentioned dynamic-effort lifting. This was the Westside Barbell inspired method coined by Louis Simmons involving the use of lower percentages of a lifter’s one rep max moved with maximal speed/faster than normal bar speed. The idea was that if you moved a slightly lighter weight, faster, you could develop power that contributed to gains in the overall strength output these lifters were chasing.

For team-sport athletes, however, we are ultimately “chasing,” improvements in speed and power output, so this type of lifting would be done to augment performance in these areas. Additionally, technology such as the Vitruve encoder and system can make it so we are not just guessing based on estimated percentages, but getting exact speeds that correspond to the desired speed ranges we want to achieve and the exact loading we would use to reach these numbers.

Again, the specifics of these numbers will be explained further down the line, but the main goal now is for you to understand that we need to improve how much force we can exert in shorter amounts of time to have the most carryover to the power driven aspect of team-sport.

To do so, we can utilize velocity based training where the loading we use is determined by the speed in which we desire to move, and the range of speed we desire to achieve is based on the varying spectrum of force and velocity.

Basically, we can work with more force and less speed OR less force and more speed and this can be largely driven by:

Athlete needs

Time of year

Goal of a certain block or period of training

Training age

Biological age

As we go along, we will discuss the implications each of the above factors will have on this decision making as well as a deep dive into all areas of this force velocity curve and how it connects to bar speed, loading and feedback given by Vitruve.

This is where Vitruve comes in!

After we have an understanding of the speeds we would like to move and the goals we are trying to accomplish, we can properly utilize the training compass that is Vittruve.

Do not make the mistake of thinking that technology such as this can do everything for you and take training and programming to the next level alone. This tool is used best by a coach or athlete that understands the things discussed in this blog and the intricacies of what we will discuss in the coming week. It is best used as something that can help us be EXACT in our prescription of load and EXACT in the feedback we get on a given athlete, lift or training session.

The Vitruve encoder is going to amplify a coach who can understand the foundations and principles of velocity based training and use it to ensure accurate measurements, rep by rep feedback and the ability to most accurately prescribe loads to individual athletes.

Once you understand why and how you would select the various load/speed ranges you want to train in and WHY you are using these ranges, the Vitruve is simply the best way to ensure these loads and speeds are accurate.

Now that you have an understanding of WHY velocity based training is important, stay tuned for my next blog addressing how to: “Use velocity based training in YOUR program, removing guess work and relying on a data system to gauge athlete progress.”

Using velocity based training in YOUR program, removing guess work and relying on a data system to gauge athlete progress. Understanding Velocity Based Training- Part 2

Now that you have a basic understanding of the origins of velocity based training and a broad view of what it is and how it works, it is time to dig a bit deeper.

As I discussed in part one of this blog series, team-sport athletes MUST do more than just traditional strength training after they have built a substantial base and level of adequate strength. Yes, velocity based training involves the idea of using bar speed measurements to help guide load selection and foster accurate training ranges to build various ranges of power, but where do we go from here? Now that this foundational understanding of the concepts have been built, it is time to discuss the idea of using velocity based training in YOUR program, removing guess work in training and relying on a data system to gauge athlete progress!

How Velocity Based Training Can Coexist with Traditional Strength Training

Before we get into the nuance of numbers, velocity ranges and what it all means, let’s start with a foundational component of actually applying velocity based training into your training schedule. Can velocity based training coexist with traditional strength training? Absolutely!

We discussed in part one how velocity based training is the idea of dynamic-effort training (moving lighter loads FASTER) but doing so with technology that allows you to get rep-by-rep feedback on the speed of each repetition so we can use loads that are as accurate as possible for the goals we are trying to accomplish.

So, the concept here is essentially how can we make this dynamic-effort training coexist with traditional strength training in our weekly training schedule? I will keep this brief, but say this first. You SHOULD NOT utilize this type of training until you have built an adequate base and body of work with typical strength training and built your strength to above average level. This will be different for everyone. Some talk about getting lifts to 2x your bodyweight in load, others talk about 3x your bodyweight in load. Some of these ranges differ depending on the exercise you are doing or who you talk to.

What is a very easy rule of thumb you can use here? When dealing with team-sport athletes, sprint speed and jump height are two of the most important numbers we look at in terms of what we are trying to improve. So, simply enough, track these numbers and look at the improvement in overall strength/added load to a max lower body lift. Are speed and strength numbers continuing to trend upwards? Great, keep getting stronger. Once the trend begins to slow or no longer exist, it may be time to look elsewhere.

When dynamic-effort lifts/VBT should be done in a weekly training schedule

When we say elsewhere, we mean dynamic-effort lifting (to build power) and velocity based training to track this dynamic-effort lifting and help us find the best loads to work in the ranges we desire.

Let’s use a four day training week here as an example in a training split where we do both dynamic-effort and maximal-effort lifting (fast lifts and traditional heavy lifts).

Training Day 1 (Lower Body Dynamic-Effort)

Warm-up/Prep Work

Speed Training

Plyometric Training

Primary Lifts (Dynamic and done with Vtiruve Encoder)

Potential Supplemental Lifts (Can also be dynamic and done with Encoder)

Accessory/Support Lifts

Training Day 2 (Upper Body Dynamic-Effort)

Warm-up/Prep work

Upper body plyometric/ballistic training

Primary Lifts (Dynamic and done with Vtiruve Encoder)

Potential Supplemental Lifts (Can also be dynamic and done with Encoder)

Accessory/Support Lifts

Training Day 3 (Lower Body Maximum-Effort)

Warm-up/Prep Work

Primary Lifts (Traditional strength focus, 1-5 repetitions)

Supplemental Lifts (Traditional strength focus, 1-5 repetitions)

Accessory/Support Lifts

Training Day 4 (Upper Body Maximum-Effort)

Warm-up/Prep Work

Primary Lifts (Traditional strength focus, 1-5 repetitions)

Supplemental Lifts (Traditional strength focus, 1-5 repetitions)

Accessory/Support Lifts

You can see how we have two days focusing on traditional heavy lifts and two days focusing on lighter, albeit FASTER lifts. Yes, I find it best to compliment speed and jump training with this dynamic-effort lifting as it is a bit closer in speed AND will build power to compliment the desired improvements we are seeking to make in sprint and jump output.

Now that we have a handle on this, how do we go about finding the optimal ranges to work in? What are the ranges? What do they mean and when should you use them? Let’s talk about it!

Ranges Involved in Velocity Based Training and No Longer Working off Arbitrary Percentages, Having Tech to Tell Us EXACT Numbers

So we now know when we should be doing velocity based training, but what type of ranges should we use, what speeds should we be working with and what do these ranges correspond with?

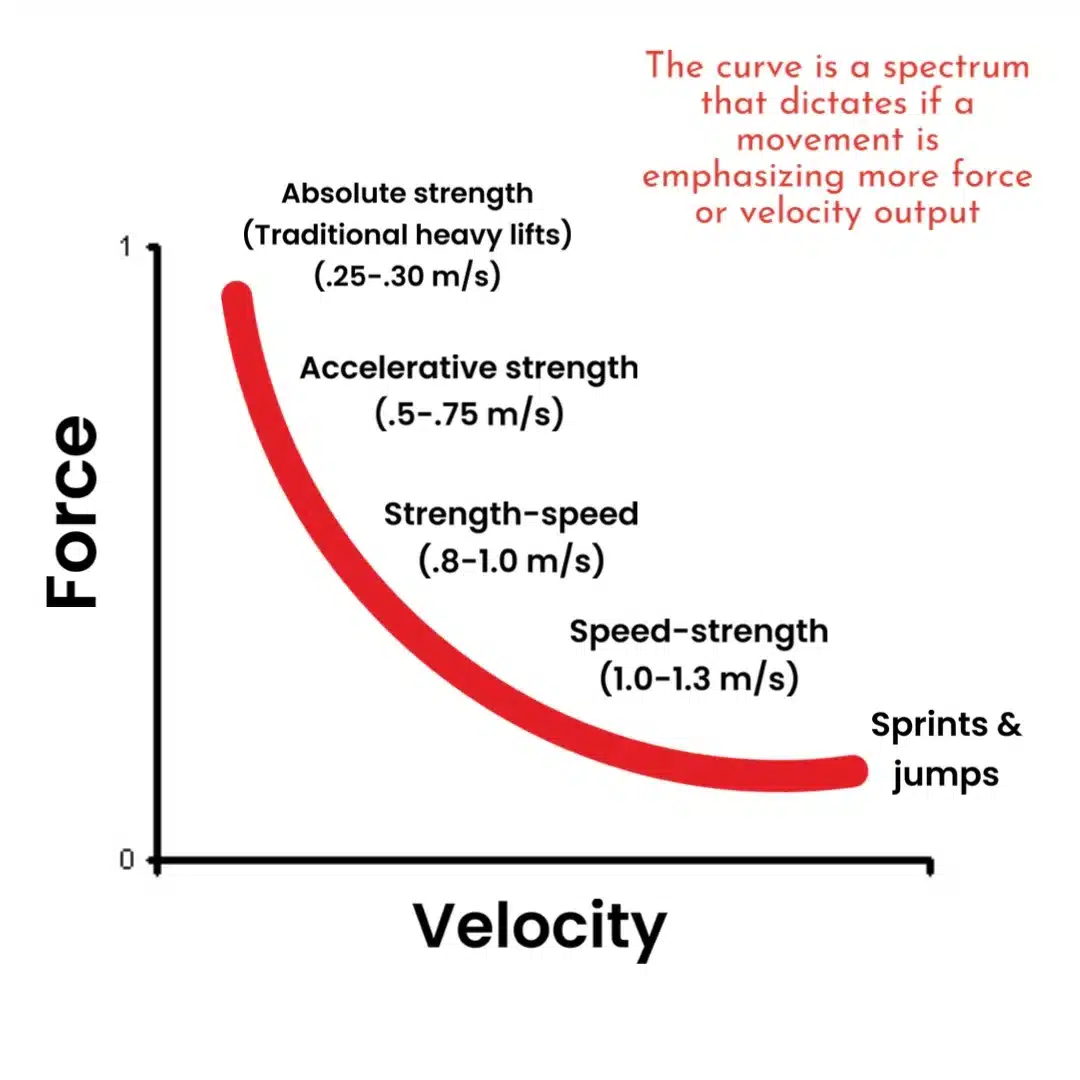

I made this chart to help break it down SIMPLY so you leave this article with the essentials and understanding you need.

To start, understand that all training is a spectrum and deals with varying levels of force or velocity output. Depending on the loads we use in training, training can either elicit more force or more velocity. Extremely heavy strength training will be very focused on force output and sprints and jumps will be very focused on velocity output.

In between those things are varying loads and speeds that address different needs. As you work down the curve, weights get lighter and speeds go higher, and you can use these different loads based on what you are trying to accomplish or what you need.

Accelerative Strength

These will be lifts where there is still a fair amount of weight involved and the bar is moving fairly slowly, but it is less weight and faster than traditional strength training to help us build higher force outputs in smaller amounts of time.

This is a great option to replace standard strength training when an athlete has sufficient experience.

This is also a good option for an athlete who seems to lack sufficient force output in their sprints or jumps.

You will see the speeds for this range above. A good starting point here would be anywhere from 70-80% of your estimated lifting max.

Strength-Speed and Speed Strength

These two ranges are the purest form of dynamic-effort lifting and involve the ideal blend of speed and load to build POWER.

Remember, as we discussed in part 1, power is simply the idea of force x velocity.

This is a GREAT range to build rate of force development, which is the ability to produce high amounts of force extremely rapidly.

You will see the speeds for this range (strength-speed) above. A good starting point for strength-speed would be anywhere from 55-65% of your estimated lifting max.

You will see the speeds for this range (speed-strength) above. A good starting point for speed-strength would be anywhere from 45-55% of your estimated lifting max.

We are going to continue to get into this as we go, but an athlete should be evaluated on a basis of things like sprint and jump speed and then we use the performance in various areas of those metrics to determine which lifting velocity ranges can benefit the athlete most.

We can also determine which ranges to use based on an overall outlook of the time of year and whether the athlete is in-season or in the off-season.

How Vitruve can give INSTANT feedback AND a history of performance to drive decision making and determine various improvements

The benefit of having a Vitruve encoder is to get by the rep exact feedback on each repetition and go beyond estimates of one rep maxes to find training weight.

I generally advise that estimated maxes can be a good starting point, but you would then put the encoder in the fold and get exact speeds so you can adjust and find the most accurate loads. Further, the entire name of the game is producing more and more force in the same or less amount of time. Using an encoder can help us continue to find new loads based on performance. If you move the load faster than the desired speed for that range, you can add MORE WEIGHT, which is fantastic for improving this ability to produce more force in a shorter amount of time.

Obviously, there is the fact that the encoder is going to give you speeds to ALSO determine if you are going too heavy with the load for the speed you want to obtain.

Yes, this is where the Vitruve encoder comes in to turn our estimates and training based on what seems to be the right weight to an exact science!

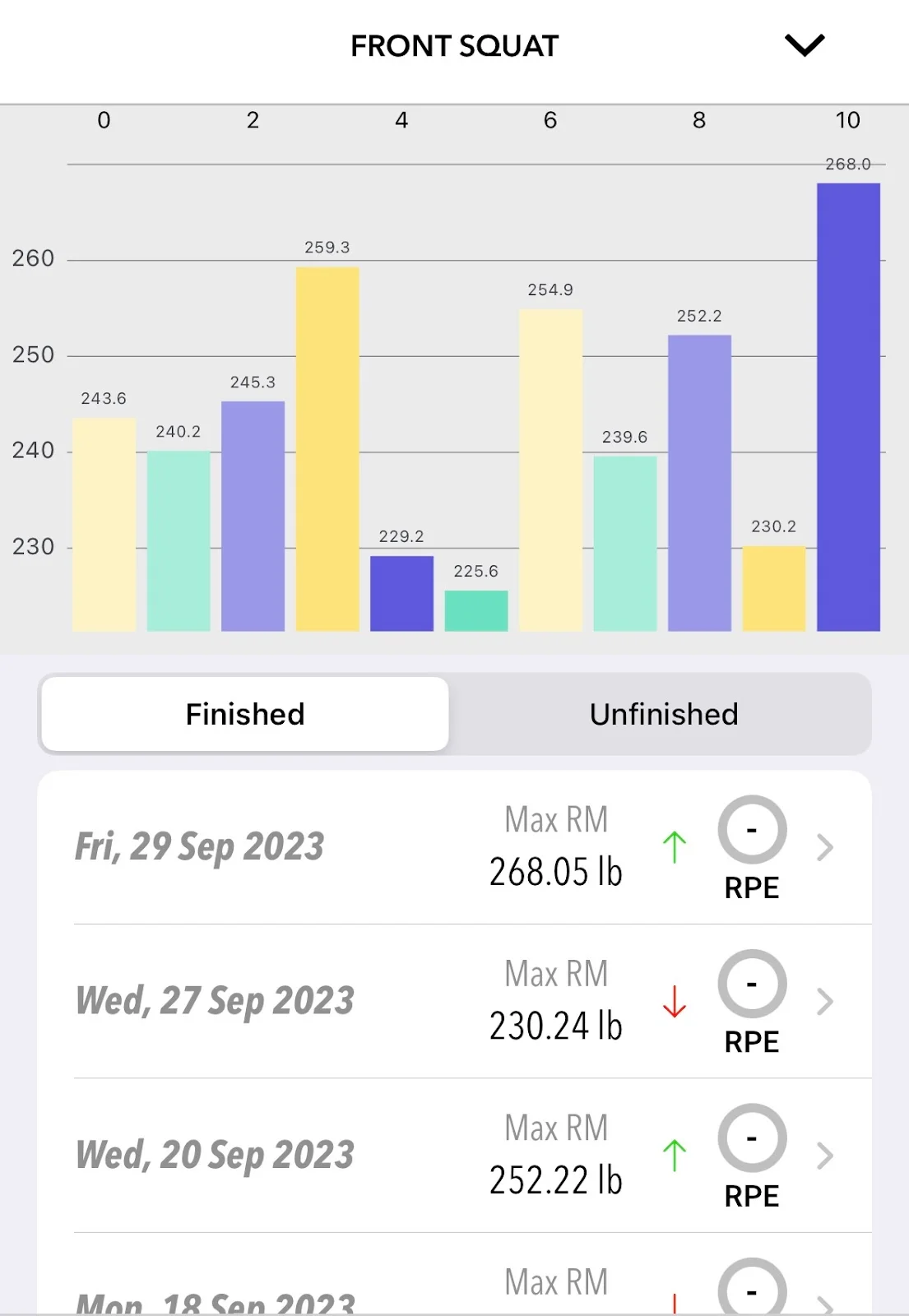

What’s even better? Vitruve provides us with easy access to our training history so we can track progress beyond just standard heavy lift numbers!

Look towards our next installment of this series where we discuss the specifics of everything you need to know about these velocity zones!