5 de January de 2024

The Correct Bar Path in Bench Press

The Importance of Executing the Correct Bar Path in Bench Press

When it comes to improving in technical exercises like bench press, we must look beyond the classic training variables such as intensity or volume. The bar path in bench press is one of the technical elements that will help us progress much faster in our lifts, in addition to avoiding discomfort and injuries. Small deviations in the bar path in bench press can lead us to a personal record or to fail a lift with an “easy” load for us.

This is compounded by the involvement of the shoulders, which are more prone to injuries and discomfort if they are not positioned correctly in bench press. The bar path in bench press may seem unimportant, but there are small details such as using a grip width of 165% to 200% of the biacromial width that allows the lifter to move heavier weights than a narrower grip (McLaughlin, 1984; Wagner et al., 1992). Other technical aspects such as leg drive, lumbar arch, or the intention to “break the bar” with an isometric external shoulder rotation while performing bench press also come into play. In this article, we will not delve into all of them, but we will focus on the bar path in bench press to use biomechanics to our advantage and lift more weight or move it faster.

Preparation of the Bench Press Position

Before performing the bar path in the bench press, we must start from a solid and stable position. To do this, we will position ourselves on the bench with the neck in a neutral position and the head always supported on the bench without lifting it. We will retract the scapula (adduction + internal rotation + depression), thinking that we have to bring them together as if we had to hold a pencil between them and take them to the back pocket of the pants.

The shoulders will perform an isometric external rotation as if we wanted to split the bar in two, thus making the elbows approach the sides to prevent them from opening during the movement. We will grip the bar at a distance of between 1.5 and 2 times the biacromial distance to exert more force (Larsen et al., 2021). In addition to the neck and shoulders, the buttocks should not lift off the bench, but the lumbar area can, so if we do not have problems in that area, we will look for a natural physiological curvature in which a hand can pass between the bench and the back.

The feet are the last part of the body that should also be supported on the ground, according to powerlifting rules, but also because this allows us to produce more force in the lockout (Van Every et al., 2022). When executing the bench press, the feet will push the ground forward, but without moving from their place. We will seek a support that allows us to start exerting force from the feet, without lifting them off the ground, and knowing that the buttocks cannot lift off the bench either.

Movement in the Bench Press

Once we are properly positioned on the bench and our body is a solid block, we will proceed to lift the bar by pushing it upward and forward, similar to the movement of a pull-over. In this way, we will already be prepared in the initial position of the movement with arms fully extended using the grip mentioned in the previous section and all structures tight and in place (throughout the article, we will refer to this position as point A). Now it’s time to take in as much air as possible to increase overall stability by increasing internal pressure, as well as slightly reduce the range of motion of the bar if we compete in powerlifting.

Now, we are ready to begin lowering the bar and initiate the bar path in the bench press during the eccentric phase. One detail that may be useful is to think about the moment when the chest goes toward the bar instead of the bar toward the chest, but always without lifting the head, buttocks, or feet off the ground. We will lower the bar with a controlled motion towards a specific point on the chest that will determine the descent line of the bar path in the bench press.

[banner_device_1]

The point of contact on the chest should be the one that protrudes upward the most, typically the transverse line between the nipple and the height of the lower end of the sternum. The reason for this is that we save range of motion in the first place and can apply more force in the ascending phase when our levers are in that position. This point will depend on the athlete’s anatomy, as if they have shorter arms, they will bring the bar closer to the head, and if they have longer arms, they will bring the bar closer to the hips (Mausehund & Krosshaug, 2023). During the descent phase, the bar path in the bench press will form a straight line, but not towards the ground, but diagonally towards the optimal point of chest contact.

The best way to determine the optimal point of bar contact on the chest is to apply chalk to the bar so that when it touches the chest, it leaves a mark at the exact point of contact. In a beginner, we will find that the white line is very wide because the support point changes with each repetition, which means there are many different contact points, and thus the shirt will have chalk in more areas. An advanced bench press athlete will have a much finer line because the bar will always go to the same point. Throughout the article, we will refer to point B as the point where the bar is touching that optimal contact point on the chest.

The last part of the movement is the concentric phase in which we must bring the bar from the chest (point B) to the starting point or point A. We will do this with the maximum intentional speed possible and with a non-vertical, but diagonal movement towards the face at the start, as this allows us to apply more force. For some authors, there is even an almost purely horizontal initial movement that brings the bar from the chest to the shoulder joint (Lawrence et al., 2017). After that initial push to lift the bar off the chest, we will end in the same starting position, thus making the bar path in the bench press draw an inverted “J”.

Biomechanical Explanation of the Bar Path in Bench Press

Eccentric or Descent Phase

An image is worth a thousand words, so we will accompany the text with images from perhaps the best resource available to understand the intricacies of the bar path in bench press, the book “Bench Press More Now: Breakthroughs in Biomechanics and Training Methods” by Thomas McLaughlin (McLaughlin, 1984). It is an old book, hence the quality level of its drawings, but to this day, it is still used to describe the shape of the bar path in bench press and the reasons behind it.

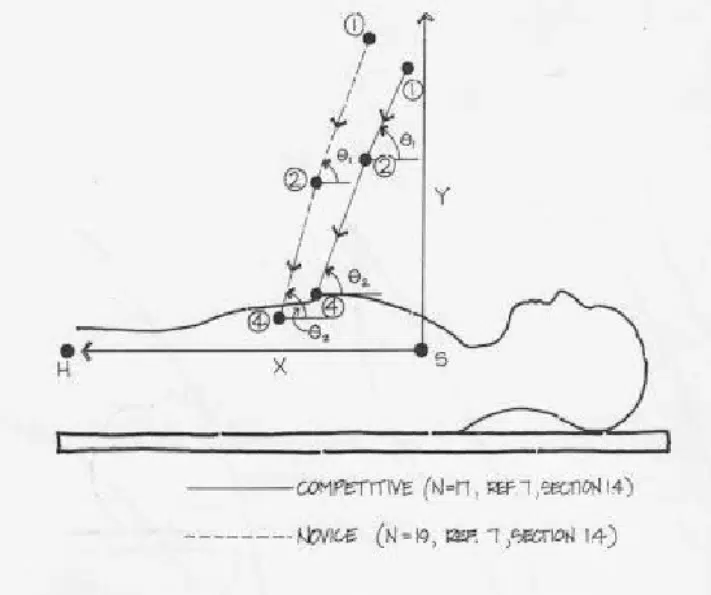

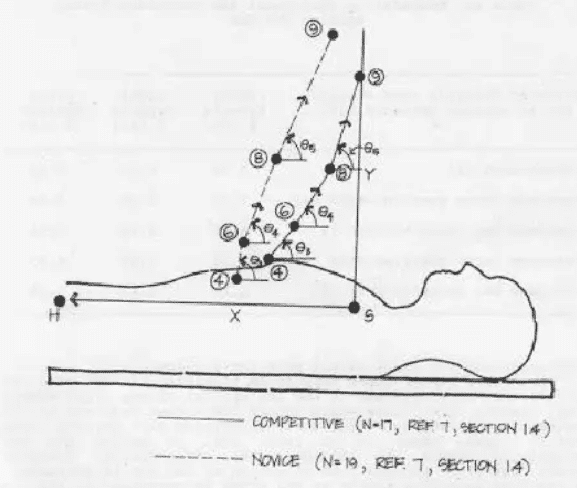

In the previous section, we detailed that the eccentric phase (from point A to point B) of the bar path in bench press is not straight but follows a slightly curved movement, generally a diagonal line on the descent until we touch the chest at the optimal point of contact. This part of the bar path in bench press is straightforward, but it changes when we perform the concentric phase to bring the bar from point B to point A. One of Thomas McLaughlin’s images shows the difference between beginner athletes (dotted line) and advanced athletes (solid line). Beginners usually start from a position further away from the head and bring the bar closer to the hips, while advanced athletes end at a different point on the chest that will help them later in the concentric or lifting phase.

Concentric or Upward Phase

In the concentric phase, the movement is not only vertical but also has a horizontal component. The concentric phase begins with the bar resting at the optimal point on the chest, and from there, we push the bar toward the head first and then move it upward until fully extending the arms to finish at the same point where the repetition began. Experts define the bar path in the bench press during the concentric phase as an inverted “J,” as we first make an almost horizontal movement of the bar towards the shoulders (the “tail” of the “J”) and then push upward (the “stem” of the “J”).

[banner_guide]

We can see this inverted “J” in the following image by McLaughlin, again comparing beginner athletes with experts. While we may make some mistakes during the descent phase, any error during the ascent phase will cause us to fail the lift or make it much more difficult. The dotted line in the image shows how beginner athletes perform an almost straight line in the concentric phase, while advanced athletes perform that inverted “J,” first bringing the bar to the head and then pushing it upward.

Why Complicate Matters When We Can Push Straight Like Beginners?

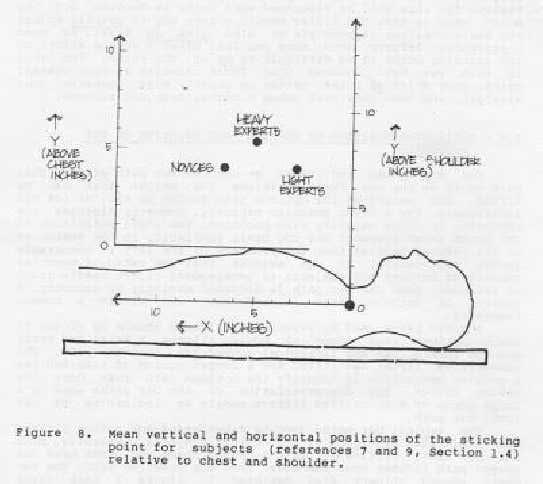

McLaughlin’s research found that the bar path in bench press directly influences lift failure. The reason is that depending on how the bar path in bench press is, we can apply more or less force at the weakest point of the lift. The main goal of moving the bar in an inverted “J” shape during the concentric phase is to be as strong as possible at the most challenging point of the movement.

McLaughlin exemplifies this with the following image, which shows where the sticking points are based on the athlete’s level. Beginners have that sticking point far from the shoulders, which means, due to complex biomechanical reasons involving levers and arm moments, they can apply less force than if the bar were closer to the shoulders. This creates the perfect storm where we reach a critical point in the bench press, but we cannot apply much force. The result will be a high probability of failing the lift. Advanced athletes had the weak point or sticking point closer to the shoulders, a region where they could apply more force than if the load were closer to the hips.

To visualize it better, imagine you have to lift a 100 kg stone from the ground. The most effective way would be to place the stone between our legs and lift it as close to the body as possible, right? If instead of doing it this way, we wanted to lift the stone away from the body, it would cost us much more, and we might not even be able to lift it. The same goal of lifting the stone changes completely depending on how close or far it is from our body.

Similarly, just as we would fail to lift the stone, or it would be much more difficult, if it is far from the axis, the same will happen with the bench press when the critical point of the lift occurs when the bar is far from the axis, in this case, the shoulder joint. A lift fails because of weakness in the critical area of the bench press, not because of general weakness. A “weak” person who performs a bar path in the bench press in the form of an inverted “J” and takes advantage of biomechanical advantages will be able to lift more weight than a “strong” person who does not take biomechanics into account and reaches the critical point of the lift being able to apply little force.

[banner_device_2]

Biomechanics and the Sticking Point are Key in Strength Lifts

Our body is filled with anatomical levers everywhere, resulting in different force moments. This aspect is very complex, but it can be summarized as follows: the closer the bar is to the shoulder at the beginning of the concentric phase, the less angular rotation we have in the joints, which favors us biomechanically. That’s what happens with the bar in bench press, because if we separate the bar too much from the shoulders, we may lift it off the chest at the beginning of the concentric phase, but at the sticking point, it will be very difficult for us to accelerate it because, like the stone when it’s far away, biomechanics will work against us.

On the contrary, if we draw that inverted “J” with the bar and bring it closer to the shoulders at the beginning of the concentric phase, we will have to exert more force at the beginning, but it will be easier for us to overcome the sticking point because biomechanics will work in our favor. You can see the bar path in bench press in videos of professional powerlifters like Dan Green, where if you pause and watch it several times, you can realize the nonlinear movement of the bar.

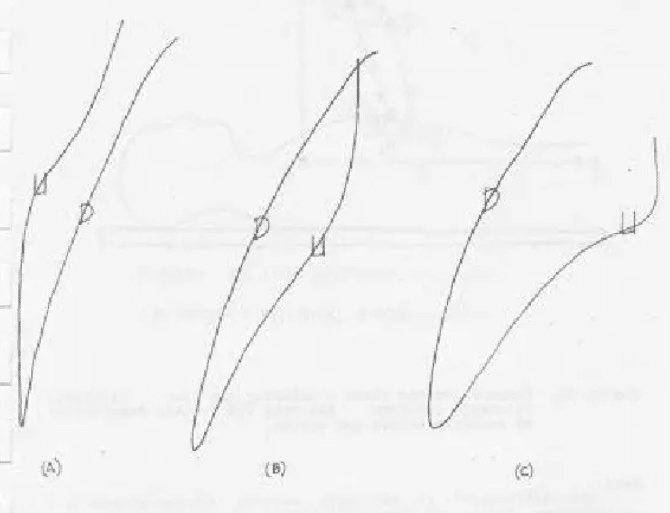

McLaughlin also depicted this in his book several decades ago, comparing a beginner lifter (left path) with two professionals: Mike Bridges (middle path) and Bill Kazmaier (right path). The letter “D” indicates the descent line, and the letter “U” indicates the ascent line. The beginner lifter lifts the bar straight and significantly away from the shoulders. Mike Bridges performs a slightly “J-shaped” ascent, but it is Bill Kazmaier, the path on the right, who most clearly shows the inverted “J” in the ascent, bringing the bar as close as possible to the shoulders to take advantage of the biomechanical benefits and be able to apply maximum force at the critical point of the lift.

References

Larsen, S., Gomo, O., & van den Tillaar, R. (2021). A Biomechanical Analysis of Wide, Medium, and Narrow Grip Width Effects on Kinematics, Horizontal Kinetics, and Muscle Activity on the Sticking Region in Recreationally Trained Males During 1-RM Bench Pressing. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2, 637066. https://doi.org/10.3389/FSPOR.2020.637066/BIBTEX

Lawrence, M. A., Leib, D. J., Ostrowski, S. J., & Carlson, L. A. (2017). Nonlinear analysis of an unstable bench press bar path and muscle activation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(5), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001610

Mausehund, L., & Krosshaug, T. (2023). Understanding Bench Press Biomechanics – Training Expertise and Sex Affect Lifting Technique and Net Joint Moments. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 37(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004191

McLaughlin, T. M. (1984). Bench Press More Now: Breakthroughs in Biomechanics and Training Methods. Author. https://books.google.es/books?id=bOpSHQAACAAJ

Van Every, D. W., Coleman, M., Plotkin, D. L., Zambrano, H., Van Hooren, B., Larsen, S., Nuckols, G., Vigotsky, A. D., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Biomechanical, Anthropometric and Psychological Determinants of Barbell Bench Press Strength. Sports, 10(12), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS10120199/S1

Wagner, L. L., Evans, S. A., Weir, J. P., Housh, T. J., & Johnson, G. O. (1992). The Effect of Grip Width on Bench Press Performance. International Journal of Sport Biomechanics, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSB.8.1.1