8 de January de 2025

Repetitions in Reserve (RIR): All You Need To Know

What’s RIR in Weightlifting?

Repetitions in Reserve (RIR) is a reliable tool for prescribing strength training load (Lovegrove et al., 2022). As the name suggests, RIR refers to the number of repetitions you leave undone before reaching muscle failure. This tool was originally created in “The Reactive Training Manual” in 2008 for use in prescribing loads in weightlifting (Greig et al., 2020). Zourdos and colleagues introduced repetitions in reserve in the scientific literature (Zourdos et al., 2016), providing a more in-depth and precise explanation of what RIR means in weightlifting.

Each load allows you to perform a certain number of repetitions per set before reaching muscle failure, which means you can’t complete a repetition. RIR refers to the number of repetitions remaining before reaching that muscle failure. Imagine you can do eight repetitions with 100 kilograms in bench press, but you only complete four repetitions in a set. This indicates that you left four repetitions in reserve until muscle failure, so we would say that this set has an RIR of 4. If, instead of leaving four repetitions in reserve, you leave two repetitions undone before reaching muscle failure, the RIR for that set would be 2. This continues down to an RIR of 0, which means you’ve completed all possible repetitions, and if you attempt another set, you won’t be able to complete it, reaching muscle failure.

RIR 0 Isn’t The Same As Muscle Failure

RIR is always accompanied by the number of repetitions in reserve we have left, unless we reach muscle failure, where we have done more repetitions than we could and that’s why we’ve failed. This difference is subtle but makes a significant difference in fatigue. With RIR 0, we complete all possible repetitions without leaving any repetitions in reserve, but we complete all attempted repetitions. Muscle failure goes further, and when we’ve already completed all possible repetitions, we attempt one more, which often leads to significant fatigue. Therefore, even though RIR 0 and muscle failure may seem the same, they aren’t

So, Why Bother With RIRI In Weightlifting?

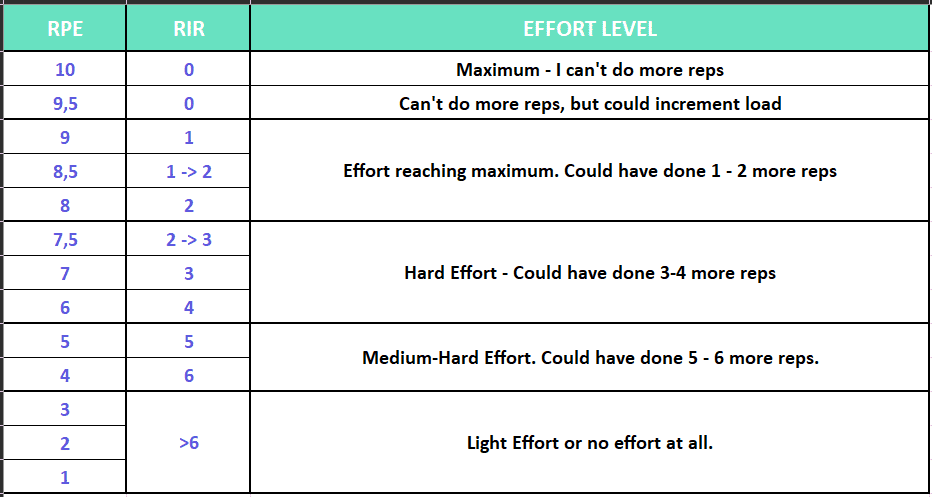

In training prescription, we’ve got some subjective effort scales like the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) and Reps in Reserve (RIR). These tools help figure out how hard an exercise really is for an athlete. RPE was originally meant for tracking aerobic workouts, but now it’s used in strength training too (Borg, 1970). RPE uses ratings from 1 to 10, where 1 is super easy, and 10 is as tough as it gets (Yamauchi, 2013). You can use the RPE scale for the whole session or rate each set individually. But there are some limitations and inaccuracies when it comes to measuring the true effort (Hackett et al., 2012).

On the other hand, Reps in Reserve (RIR) are more precise in gauging the effort, whether you’re a beginner or an advanced athlete (Ormsbee et al., 2019). Some folks have compared RPE and RIR to have two quick and accurate tools to assess an athlete’s effort level. Here’s a nifty table from Joaquín Vico Plaza, a writer for Vitruve, adapted from Zourdos et al. (2016).

Table from: Vitruve Writer, Joaquin Vico Plaza’s adapted from Zourdos et al., (2016)

The goal of using Reps in Reserve (RIR) is to determine how close or far we are from muscle failure, which indicates the level of effort in each set. In the table above, you can see that an RIR of 0, associated with an RPE of 9.5 – 10, represents maximum effort, meaning it leads to the highest possible level of fatigue. However, as you leave more repetitions in reserve, the effort decreases. Depending on your goal, you might aim for an RIR closer to zero or farther from muscle failure.

In a nutshell, RIR is an alternative method to the percentage of 1RM often used to determine loads in strength training (AREDE et al., 2020). The difference between using percentages and closed repetitions with 1RM is that RIR equalizes the stimulus for all athletes. This means that an athlete can perform more repetitions with a given load, while another athlete might perform fewer repetitions, but they both exert the same effort. However, if you ask both of them to perform the same number of repetitions, it might feel like a tough effort for one and a moderate effort for the other. RIR levels the efforts by ensuring that all athletes, regardless of the actual number of repetitions they complete in their set, exert the same effort by using the same number of repetitions in reserve (RIR).

How Do You Go About Prescribing Strength Training using RIR?

When it comes to prescribing strength training, you often find a specific number of sets and repetitions with a given weight, but no sign of RPE or RIR. If you want to introduce these subjective effort scales into your planning, you should make a note of it on the template. For example, if the coach wants the lifter to perform 3 sets of 10 repetitions, stopping 1 or 2 reps before muscle failure, they would prescribe it like this: “3 × 10 with RPE 8-9 or RIR 1-2.”

Then, the lifter would choose a weight that they believe they can complete for 10 reps but stop 1 or 2 reps short of muscle failure. To select the weight directly, in the next section, we describe a complex topic: the relationship between the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), Reps in Reserve (RIR), and the percentage of 1RM that you’re capable of lifting.

Relation Between RPE, RIR, 1RM%

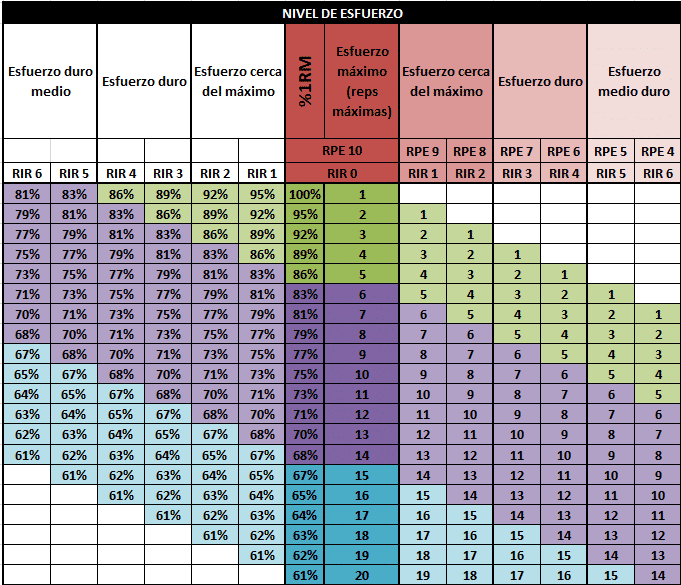

This section is complex and requires some time to understand. Take a good look at the following table, crafted by Joaquín Vico Plaza, a writer for Vitruve, adapted from Helms et al., 2016. This table links the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), Reps in Reserve (RIR), and the percentage of the one-repetition maximum (%1RM). To comprehend the table, let’s start with the dark red central part. These two central columns refer to the maximum load you can lift, which represents a maximum effort correlated with an RPE of 10 and an RIR of 0. In the left column of the dark red section, you’ll find the %1RM, with 100% being the maximum weight you can lift for one repetition. As you move down the rows, %1RM decreases, and the number of repetitions increases, always indicating the maximum number of repetitions you could do with that load.

1RM Calculator

So, you can aim for, say, 75% of 1RM, theoretically associated with 10 maximum repetitions, meaning it’s a maximum effort, or in other words, an RPE of 10 and RIR of 0. Once you’ve got that, you can move left or right on the table. If you move to the right, you can prescribe the training based on the theoretical RPE and RIR. In the top row, 100% of the load means you can do only one repetition, so there’s no option to leave any reps in reserve. However, if you select 95% of 1RM, you have the option of doing two reps, which is an RPE of 10 and RIR of 0, or you can do just one rep, leaving one rep in reserve (RIR of 1), which is associated with an RPE of 9. You can keep moving down the rows to explore different combinations of RPE, RIR, and %1RM. Remember, we’re still on the right side of the table, don’t go to the left part just yet. In this right section, you can adjust the load to work with a specific RIR or RPE.

For example, if you want to work with an RIR of 3, go to the “hard effort” column on the right and find RIR 7, which is associated with RPE 7. The first option you see is to do one rep with 89% of the load. Theoretically, 89% of the maximum load allows you to do 4 reps, so if you do just one, you’ll have three reps in reserve, which is what you were aiming for. Take your time with the table and see how each RIR tells you the number of reps to do and the load to use.

Now, if we move to the left part, we can do the same thing, but by using %1RM directly. Going to the top row, with 100% 1RM and 1 repetition in the center, as you move to the left, the load decreases. This means that if you use 95% of the load and do one rep, you’ll have left one rep in reserve, which is an RIR of 1. If you want an RIR of 2 with a single repetition, you’ll need to select a load of 92%. This way, you can keep playing with RIR and the number of repetitions. Remember, the central dark red column is your guide for moving left and right. It’s quite complex, but once you grasp it, the table will help you work with RIR accurately.

Tabla de Joaquín Vico Plaza, redactor de Vitruve, adaptada de Helms et al., (2016).

RIR vs VBT: A Subjective Measure Versus An Objective One.

In the previous sections, we discussed how using the number of Reps in Reserve (RIR) is often more precise than relying on the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) (Hackett et al., 2012). The closer we are to muscle failure, the more reliable RIR becomes because when we are far from muscle failure, it’s challenging to determine how many more reps we could do. Just as RIR outshone RPE, Velocity-Based Training (VBT) is doing the same by taking the spotlight away from RIR (Larsen et al., 2021).

Velocity Based Training (VBT) in strength training involves prescribing the load based on the speed at which we move the weights (Zhang et al., 2022). As the load increases, the speed at which we can move it decreases. This allows for an objective association between speed and proximity to or distance from muscle failure (Balsalobre-Fernández & Torres-Ronda, 2021). Considering that RIR is a subjective measure dependent on the athlete’s perception, VBT is more interesting because it provides precise results regarding the actual number of reps left until muscle failure (Larsen et al., 2021).

RIR is an accurate and reliable measure when we are closer to muscle failure, but the farther we are from it, meaning the higher the RIR, the less precise the results become (Zourdos et al., 2016). Additionally, both RIR and RPE require a learning period to truly understand what constitutes maximum, hard, moderate, or light effort and associate it with the corresponding RIR or RPE. However, VBT doesn’t require this learning curve. Instead, as you train and observe how the loss of speed in each set corresponds to the number of reps left until muscle failure, you can accurately determine how many reps you have left based on the execution speed.

For example, let’s say you’re lifting 150 kilograms in deadlift, a load that’s your 10RM, meaning you can theoretically perform 10 reps with that weight but not 11. You want to do only half of the possible reps, in this case, five reps. This means you’ll leave five reps in reserve (RIR 5), which would also correspond to an RPE of 5. In theory, this all sounds ideal, but it’s quite challenging to control such a high number of reps in reserve. It’s much easier to determine if you’re at RIR 0, RIR 1, RIR 2, or RIR 3, but beyond that, it takes a lot of experience to know for sure if you’re four, five, or six reps away from muscle failure.

To address this, VBT allows you to associate each speed with a specific number of reps until muscle failure. All you need to do is move the load until you reach a certain speed, which corresponds to the RIR you want, whether it’s RIR 5 or more. To do this, you simply need a speed measurement device like the one from Vitruve and an understanding of the association between your RM percentages, the speed of load displacement, and RIR.

Best Velocity Based Training Devices – Full Review 2025

How Many Reps In Reserve Should We Leave to Gain Muscle Mass?

Muscle mass and muscle failure have always been closely associated. The vast majority of bodybuilders train to muscle failure in each set for two reasons: it’s the simplest way to measure effort since you’re pushing to the maximum, and it often feels more satisfying to train intensely. However, it’s widely demonstrated that it’s not necessary to reach muscle failure to promote muscle hypertrophy, but being near it is important (Refalo et al., 2023). In fact, research explains that for a set to count in the total training volume, you should stay within four reps or less of muscle failure. This means that training sessions with the goal of muscle hypertrophy should have a range between RIR 0 and RIR 4 (Baz-Valle et al., 2021).

This statement has many nuances because the needs of a beginner bodybuilder are fundamentally different from those of an advanced one. Fatigue cannot be quantified in the same way with heavy or light loads. Beginners don’t need to stay as close to muscle failure, so their RIR might be four or more. The same goes for older adults, who will benefit from leaving many reps in reserve. In these populations, a specific RIR cannot be determined, but the focus should be on learning the exercises and providing minimal stimulus to achieve maximum adaptation.

The higher the number of possible repetitions, the more important it is to be near muscle failure. One common mistake made by many gym-goers is training far from muscle failure at high repetitions, which will lead to minimal hypertrophic adaptations. For instance, if you can do 35 push-ups but only do 12, the stimulus will not be comparable to doing 6 push-ups and stopping at 2. Therefore, the lower the load and the higher the number of repetitions, the RIR should be closer to zero (Lasevicius et al., 2022).

General Recommendation for RIR to Increase Muscle Mass

Helms and colleagues provide the following recommendation, which has been accepted by many other researchers (Helms et al., 2016):

To gain muscle mass, an RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) of 8-10 and RIR (Reps in Reserve) of 0-2 is the ideal range, depending on the training phase. Training with an RIR of 0 should be implemented in a way that does not potentially reduce volume in subsequent sets due to fatigue, and it should not be used for highly technical exercises. For compound movements (e.g., squats, bench press, etc.), primarily performing sets within the RPE range of 6-8 (equivalent to RIR 2-4) can be an appropriate strategy to prevent excessive muscle damage and maintain intensity in later sets.

How to Progress with RIR for Muscle Gain?

Knowing that the most recommended RIR (Reps in Reserve) for gaining muscle mass is below RIR 4, especially between RIR 0 and RIR 2 for isolation exercises, and between RIR 2 and RIR 4 for technical and compound exercises, you should aim to progress within these limits. For example, if today you can lift 100 kilograms in the bench press with an RIR of 3, but on another day, the same weight and repetitions result in an RIR of 4, the training is easier, indicating the need to increase the load.

The simplest way to progress using RIR is to gradually approach zero, which requires greater effort, even if the weight lifted remains the same. Therefore, you can gradually reduce your RIR to zero each week and then take a deload before starting again.

- Week 1: RIR 4

- Week 2: RIR 3

- Week 3: RIR 2

- Week 4: RIR 1

- Week 5: RIR 4 and start over

How Many Reps in Reserve Should We Leave to Gain Strength and Power?

While RIR (Reps in Reserve) and muscle growth are closely connected, strength and RIR have a more complex association. When training for strength, you don’t need to get as close to muscle failure as you do in hypertrophy sessions. In fact, it’s much more advisable to train further from muscle failure to gain strength and power. As mentioned earlier, RIR becomes less accurate as you move further from muscle failure, so athletes would need a deep understanding to gauge whether they are leaving five, six, or more reps in reserve (Haff, 2016).

Furthermore, when training movements with low load and high speed, such as jumps or throws, RIR can be quite complex to apply. In these situations, instead of relying on RIR, it’s recommended to use Velocity Based Training (VBT). We’ve discussed VBT as an alternative to RIR before, and while RIR is more than sufficient for muscle hypertrophy, if you aim to enhance your strength, power, and athletic performance, VBT is by far a better choice.

Velocity Based Training 【 #1 VBT Guide in the World 】

Following recommendations from authors who study VBT, it is suggested to use half or even fewer of the maximum possible repetitions. When training for strength with heavy loads, it’s relatively easy to control RIR because you’re always close to muscle failure. If your maximum reps are around five or six, even just doing a couple of reps puts you at RIR 4 or lower. The challenge arises when you use lighter loads that allow for a high number of reps but aim to do only a few.

How to Progress with RIR to Gain Strength and Power?

The use of RIR (Reps in Reserve) in strength and power training has more limitations than when used for muscle gain, although it doesn’t mean it’s not an interesting and effective tool. While proximity to muscle failure is closely related to muscle growth, this isn’t necessarily the case for strength and power. In fact, training with heavy loads close to muscle failure can lead to significant fatigue, necessitating several days of recovery. Conversely, when training with heavy loads but staying far from muscle failure, you can even train the same movement daily if you manage fatigue well.

The progression described with RIR for muscle gain doesn’t make much sense when aiming to increase strength and power. In these cases, the goal is to lift heavier loads and move them at higher speeds, rather than getting closer to muscle failure. In other words, RIR can remain constant, and progression can be achieved by adding more weight or moving the weight faster. The use of velocity measuring devices is more helpful than RIR in this context, as they show the speed at which you move the load, and you can monitor the speed you’re losing during the set to stop when you reach a certain speed drop. In fact, RIR and the speed of execution in a set go hand in hand, as the slower the speed becomes, the closer RIR gets to zero (Guez-Rosell et al., 2020; Mangine et al., 2022).

Conclusion

RIR stands for Reps in Reserve, which refers to the number of repetitions we intentionally don’t perform in a set, even though we could. This tool allows us to assess the level of effort in each set and adjust the training stimulus according to the desired level of fatigue. Instead of relying on an external measure like fixed repetition prescriptions, RIR lets us use an internal measure of effort, making it equitable for all athletes. One athlete might do 5 reps, while another does 3, but if they both agree on the number of reps in reserve until muscle failure, their effort level will be the same.

You can complement RIR with the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale and Velocity Based Training (VBT). VBT follows the same principles as RIR in terms of providing all athletes with the same internal stimulus, but it uses objective data rather than subjective judgments, enhancing its reliability. Incorporate RIR into your workouts if you haven’t already to make faster progress and manage fatigue more effectively.

References

AREDE, J., VAZ, R., GONZALO-SKOK, O., BALSALOBRE-FERNANDÉZ, C., VARELA-OLALLA, D., MADRUGA-PARERA, M., & LEITE, N. (2020). Repetitions in reserve vs. maximum effort resistance training programs in youth female athletes. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 60(9), 1231–1239. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.20.10907-1

Balsalobre-Fernández, C., & Torres-Ronda, L. (2021). The Implementation of Velocity-Based Training Paradigm for Team Sports: Framework, Technologies, Practical Recommendations and Challenges. Sports, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS9040047

Baz-Valle, E., Fontes-Villalba, M., & Santos-Concejero, J. (2021). Total Number of Sets as a Training Volume Quantification Method for Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(3), 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002776

Greig, L., Stephens Hemingway, B. H., Aspe, R. R., Cooper, K., Comfort, P., & Swinton, P. A. (2020). Autoregulation in Resistance Training: Addressing the Inconsistencies. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.z.), 50(11), 1873. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-020-01330-8

Guez-Rosell, D. R., Yanez-GarciA, J. M., Sanchez-Medina, L., Mora-Custodio, R., & Lez-Badillo, J. J. G. (2020). Relationship Between Velocity Loss and Repetitions in Reserve in the Bench Press and Back Squat Exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(9), 2537–2547. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002881

Hackett, D. A., Johnson, N. A., Halaki, M., & Chow, C. M. (2012). A novel scale to assess resistance-exercise effort. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(13), 1405–1413. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.710757

Haff, G. G. (2016). Program Design for Resistance Training. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 439–470.

Helms, E. R., Cronin, J., Storey, A., & Zourdos, M. C. (2016). Application of the Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale for Resistance Training. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 38(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000218

Larsen, S., Kristiansen, E., & van den Tillaar, R. (2021). Effects of subjective and objective autoregulation methods for intensity and volume on enhancing maximal strength during resistance-training interventions: A systematic review. PeerJ, 9. https://doi.org/10.7717/PEERJ.10663/SUPP-4

Lasevicius, T., Schoenfeld, B. J., Silva-Batista, C., de Souza Barros, T., Aihara, A. Y., Brendon, H., Longo, A. R., Tricoli, V., de Almeida Peres, B., & Teixeira, E. L. (2022). Muscle Failure Promotes Greater Muscle Hypertrophy in Low-Load but Not in High-Load Resistance Training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(2), 346–351. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003454

Lovegrove, S., Hughes, L. J., Mansfield, S. K., Read, P. J., Price, P., & Patterson, S. D. (2022). Repetitions in Reserve Is a Reliable Tool for Prescribing Resistance Training Load. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(10), 2696–2700. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003952

Mangine, G. T., Serafini, P. R., Stratton, M. T., Olmos, A. A., VanDusseldorp, T. A., & Feito, Y. (2022). Effect of the Repetitions-In-Reserve Resistance Training Strategy on Bench Press Performance, Perceived Effort, and Recovery in Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004158

Ormsbee, M. J., Carzoli, J. P., Klemp, A., Allman, B. R., Zourdos, M. C., Kim, J. S., & Panton, L. B. (2019). Efficacy of the Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion for the Bench Press in Experienced and Novice Benchers. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33(2), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001901

Refalo, M. C., Helms, E. R., Trexler, E. T., Hamilton, D. L., & Fyfe, J. J. (2023). Influence of Resistance Training Proximity-to-Failure on Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 53(3), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-022-01784-Y

Yamauchi, S. M. S. (2013). Rating of Perceived Exertion for Quantification of the Intensity of Resistance Exercise. International Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 01(09). https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-9096.1000172

Zhang, X., Feng, S., Peng, R., & Li, H. (2022). The Role of Velocity-Based Training (VBT) in Enhancing Athletic Performance in Trained Individuals: A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19159252

Zourdos, M. C., Klemp, A., Dolan, C., Quiles, J. M., Schau, K. A., Jo, E., Helms, E., Esgro, B., Duncan, S., Garcia Merino, S., & Blanco, R. (2016). Novel Resistance Training-Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(1), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001049