1 de February de 2023

All About Long-Term Athletic Development (LTAD)

What is long-term athletic development (LTAD) and why is it important?

Image taken from Brett Wharton (Unsplash)

Physical activity improves the overall health of children and young adults by reducing the risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, and suicide, among other chronic medical conditions (Washington et al., 2001). Increasing youth physical activity has become a priority for many countries, leading to the development of national statements and strategies to promote physical activity in youth (Balyi, Way, Higgs, Norris, & Cardinal, 2016). The U.S. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Physical Activity Alliance recommend that children and adolescents engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity for at least 60 minutes every day (Piercy et al., 2018).

Less than 20% of adolescents have met these guidelines during the past few years (Dunton, Do, & Wang, 2020). Those children and youth who participate in organized sports can gain additional benefits beyond those associated with physical activity alone, which include “improving confidence, self-esteem, and providing the opportunity to work on social interaction, communication, leadership, and teamwork (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). The problem arises when these young athletes specialize in a single sport at an early age, instead of using some model of long-term athletic development (LTAD). Recent studies have shown that such early sport specialization can be a risk factor for overuse injuries and burnout, in addition to missing out on learning sport patterns from other sports that will enrich the child’s sport skills in the long term (Myer et al., 2015).

Long-term athletic development models also include individuals who do not focus their future goal on elite sport, but are simply children and adolescents looking to enjoy physical activity while reaping its full benefits. Therefore, and as supported by scientific evidence (Granacher & Borde, 2017), following a long-term structured athletic development model, rather than focusing on a specific sport, will lead to better results in different fitness tests and lower risk of injury in adulthood. Moreover, additional hours of sports training do not negatively affect cognitive or academic performance, as physical activity is a great ally of the brain’s effectiveness in its executive functions (Granacher & Borde, 2017).

What does long-term athletic development consist of?

Long-term athletic development (LTAD) is a structured pathway to optimize the development of talented children into full-fledged elite athletes (Granacher et al., 2016). The most prominent model used as a basis for long-term athletic Development is the one created by Balyi and collaborators in 2004 under the name “Long-term athlete development model” (Balyi & Hamilton, 2004). The authors determine different stages of training according to an estimation of biological maturation, since chronological age varies from one child to another.

The long-term athletic development model consists of seven sequential stages based on individual maturation level rather than chronological age (Granacher et al., 2016). There are two main pathways that children and adolescents can follow: 1) “pathway to the podium” for long-term athletic development for those children who have been identified as having elite potential and want to go down that pathway; 2) “lifelong active pathway” for recreational athletes where the intent is for them to engage in physical activity throughout their lives, whether or not in high-level federated sports.

Ten factors underlying the long-term athletic development model

Image taken from Rachel (Unsplash)

A very comprehensive narrative review from 2022 established the ten factors on which long-term athletic development is based (Varghese, Ruparell, & LaBella, 2022). Those factors are drawn from two of the most comprehensive handbooks on long-term athletic development (Balyi, Way, & Higgs, 2013; Balyi et al., 2016). In the following, we will extract almost verbatim these ten factors summarized in the aforementioned narrative review (Varghese et al., 2022):

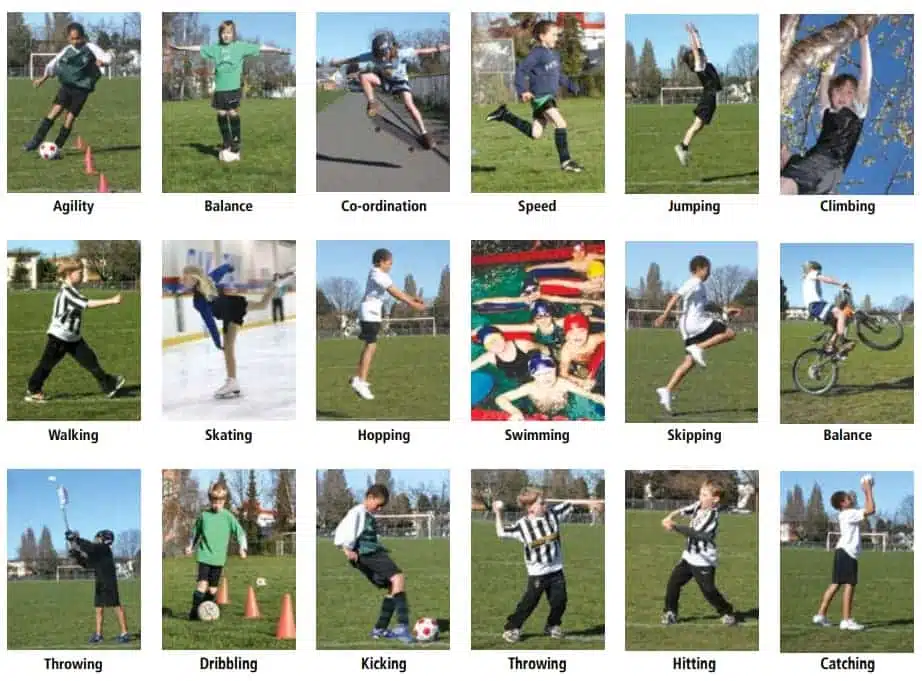

- Physical literacy: seeks participation in sports by developing motivation, ability, and knowledge to understand movement. Skills include locomotor skills (e.g., climbing, galloping, jumping), object control skills (e.g., catching, kicking, dribbling, hitting with different rackets), and balance movements (e.g., dodging, floating, ready position)

- Specialization: Sports are classified in this model as early or late specialization sports. Early specialization sports contain skills that typically peak before maturation (e.g., gymnastics, diving, figure skating).

- Developmental age: As mentioned above, chronological age is misleading because it varies from child to child. Instead, biological maturation is used with aspects such as height, weight, etc.

- Sensitive periods: Also described as “windows of opportunity” in the long-term athletic development model as the stage of biological maturity during which the ability to learn a specific skill is easier. The sensitive periods of skill, endurance and strength are based on biological maturation, while speed and flexibility are based on chronological age.

- Mental, cognitive and emotional development: These factors are important, in addition to physical development that includes understanding fair play and ethics within sport, regulating emotions during play and decisions making. Children move from exploring movement to executing movements throughout their development.

- Periodization: The planning and organization of a training program in terms of frequency, duration, and intensity that can be divided into different phases and seasons.

- Competition: development of a competition schedule. At each maturational stage there will be a greater or lesser proportion of the competitive arena, leaving the remaining percentage for training other general skills.

- Excellence takes time: developing an athlete and achieving an elite level in sport takes many years. Emphasis is placed on the 10,000-hour rule, which is a theory that a minimum of 10 years of deliberate practice is required for individuals in any field to reach the elite level. While commonly cited, this theory is not well supported by scientific data.

- System alignment and integration: Long-term athletic development should be integrated into the education and public health systems.

- Continuous improvement: The long-term athletic development model is based on the concept of continuous improvement and evolution of athlete development that requires flexibility, which is attributed to the Japanese philosophy, kaizen. Examples include incorporating current scientific evidence into training and continuing education for everyone involved in training (coaches, physical trainers, athletes, etc.).

Early stages of long-term athletic development (LTAD)

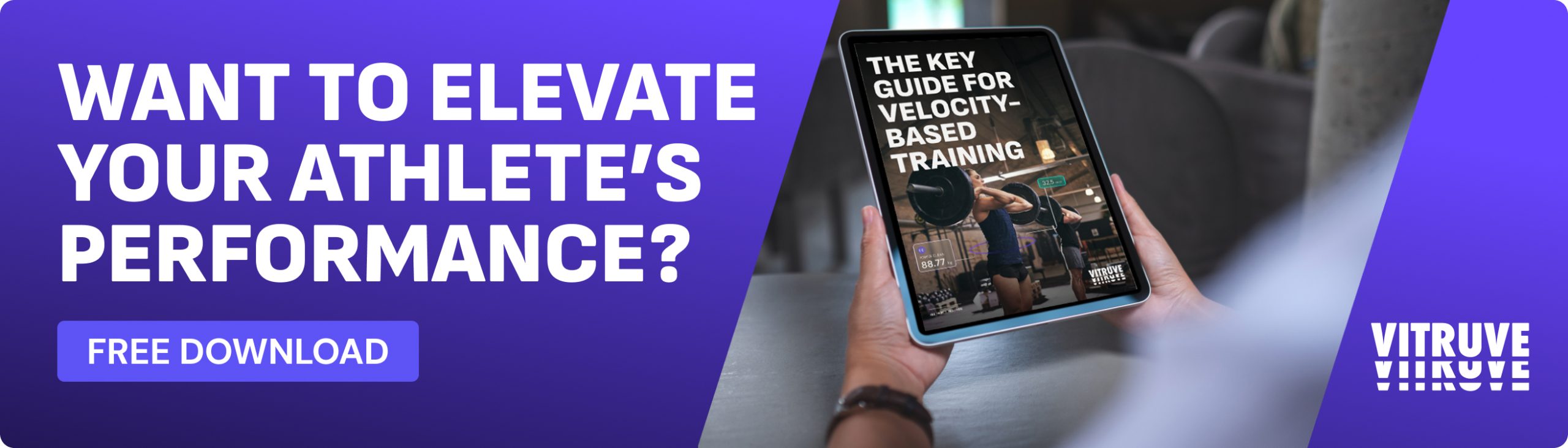

Figure extracted from (Balyi et al., 2016). Stages of long-term athletic development by chronological age

The specialized manual in long-term athletic development “Sport for Life – Long-Term Athlete Development” extensively exposes the seven stages of long-term athletic development (Balyi et al., 2016). We summarize them below, but if you are interested in this topic and want to go deeper, you can access this complete manual by clicking on this link. The first three stages focus on physical literacy and taking advantage of sensitive periods of learning, to lay the foundation for long-term performance, but above all to ensure that the contact with physical activity created in these stages lasts a lifetime.

First stage: Active start

The first stage begins between the ages of three and six, in both boys and girls, and is their first contact with physical activity. The goal is to use play to learn basic fundamental patterns, and to do so in a fun way. The child has to feel that physical activity is part of his or her daily life, not a supplement to it. At this stage the child should be physically active on a daily basis through basic tasks such as running, jumping, kicking and throwing. A very important aspect is that the game is not about winning, it is about having fun and making the child have a good time.

Second stage: FUNdamentals

From this stage onwards, the chronological ages of biological maturation in boys and girls begin to be differentiated. For boys this second stage occurs, on average, since it is always necessary to adjust to the maturation of each one, between the ages of six and nine. In girls, this stage is shorter, also starting around the age of six, but ending around the age of eight.

The first aspect to highlight of the second stage is the play on words that highlights “FUN” from the concept of “FUNdamentals”. Learning the fundamentals of any sport is not a fun task, but we as coaches must make it so. At this stage the child continues to develop skills with play and in a fun environment, and in turn should learn basic flexibility exercises, the basics of a wide range of sports (the simple rules and operation), and aspects of physical preparation such as strength training with one’s own body weight.

Third stage: learn to train

Between nine and twelve years there is the most important period before the typical “growth spurt”, which is technically called “moment of maximum speed of growth in height”. Children, on average we always speak, begin this stage around the age of nine and finish it around the age of twelve. Between the ages of nine and twelve is the most important period before the typical “growth spurt”, which is technically called the “moment of maximum growth rate in height”. Children, on average we always talk about, start this stage around the age of nine and finish it around the age of twelve. Girls start at the age of eight and finish after their eleventh birthday. We emphasize again that these values are a generic guideline, but the timing of each stage should be based on the biological maturation of each child. A very simple example of biological maturation is menarche in girls, which occurs earlier in some women and later in others. This stage coincides with the onset of puberty and extends throughout this adolescent maturation process.

In the list of the ten factors on which athletic development is based, we find the factor “sensitive periods”. This is one of the most important times to learn specific skills that will be the basis for adult performance. At this stage the child will learn general sports skills, as well as classic concepts such as warm-up, cool-down, stretching, etc. This third stage is key in physical literacy, and will help the child gain the confidence, motivation and physical foundations to enjoy sports throughout his or her life.

The learning to train stage includes more complex physical preparation exercises such as jumps, changes of direction, general agility, and even mental skills such as visualization, which is often forgotten in these stages, but is so important in sports performance.

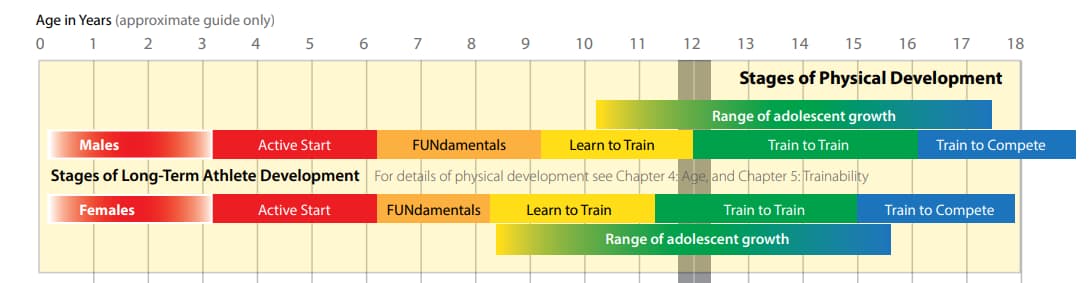

Stages of long-term athletic development

Image taken from (Balyi et al., 2016).

The seven stages of the long-term athletic development model: 1) active initiation; 2) FUNdamentals; 3) learning to train; 4) train to train; 5) train to compete; 6) train to win; 7) active for life, which has three paths: a) competitive for life; (b) lifetime assets; c) Coaches for life

Fourth stage: train to train

The fourth stage of long-term athletic development occurs in the midst of adolescent growth, extending in boys between the ages of 12 and 16, and in girls between approximately 11 and 15 years of age. The objective of this stage is to take advantage of this sensitive period for the main physical qualities such as strength and endurance. The wide range of sports is gradually narrowed to specialize in one or two sports in which the athlete excels and, of course, likes. The focus is still on having fun while improving the skills learned in previous stages, but we must focus more and more on a specific sport and their physical needs.

Fifth stage: train to compete

The importance of competition increases in this last phase of adolescence, where we are already focused on one or two sports in which we will constantly compete. Depending on the sport, the adolescent will focus on positions specific to his or her discipline and the gestures it requires. In this fifth stage we will dedicate 60% to sport and competition specific training, leaving the remaining 40% for the development of general technical skills.

Sixth stage: train to win

Long-term athletic development comes to an end with this final stage in which the athlete focuses on training, competing and recovering from a sport at the highest possible level. Sport specific aspects such as decision making and specific skills will be trained from here on out. The objective is to consolidate all the previous years of training in which the child has learned to enjoy the sport, has enriched his quality of movements by playing with his hands, with his feet, throwing, shooting, etc.

Seventh stage: active for life

This seventh stage will depend on the path the athlete wants to follow. If he or she has progressed through all of the previous stages and has achieved high proficiency in his or her sport, he or she may have joined a college team or already be competing at a high level. These individuals will be “competitive for life” and will continue on their path to high performance. On the other path are individuals who like physical activity and sport, but do not want to compete and prefer to take physical activity as a recreational lifestyle. These people will be “active for life”.

Whichever path they follow, the important thing is that they have followed all the previous stages of long-term athletic development to have established the pleasure of physical activity, with all the physical, social and mental benefits that this entails. A third path can also be walked and that is the path of the people who will be “coaches or sports leaders”. This path is vital to detect children with great potential who can reach the sports elite, as well as to recruit as many children as possible so that they will be active throughout their lives.

Qualities to focus on over the years of long-term athletic development

Image taken from Kenny Eliason (Unsplash)

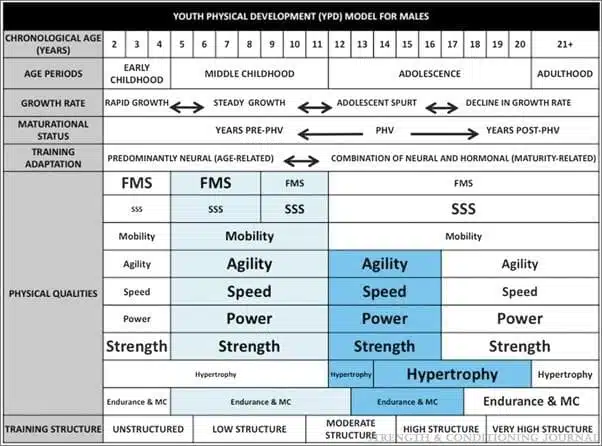

In 2012, Lloyd and Oliver created the “Youth physical development model: a new approach to long-term athletic development” (Lloyd & Oliver, 2012). This model follows the same guidelines that we have discussed so far, trying to make the child’s maturation state the basis that dictates the physical quality to enhance according to the “windows of opportunity”. In these sensitive periods, children and adolescents have the greatest potential to improve one quality or another. If we do not take advantage of these windows, we will be limiting future athletic potential since we will no longer be able to go back and take advantage of them.

The authors base these sensitive periods on the PHV: the maximum height velocity. By taking weight and height data throughout childhood and adolescence, we can know the speed of maturational development of each individual. The maximum speed of growth in height is associated with the evolution of performance (Lloyd & Oliver, 2012). On the other hand, PWV (peak weight velocity) is a developmental phase characterized by rapid increases in muscle mass as a result of increased sex hormone concentrations (Ford et al., 2011). By objectively measuring rates of change in height and body mass, it is suggested that children can be trained according to biological status rather than chronological age (Lloyd & Oliver, 2012).

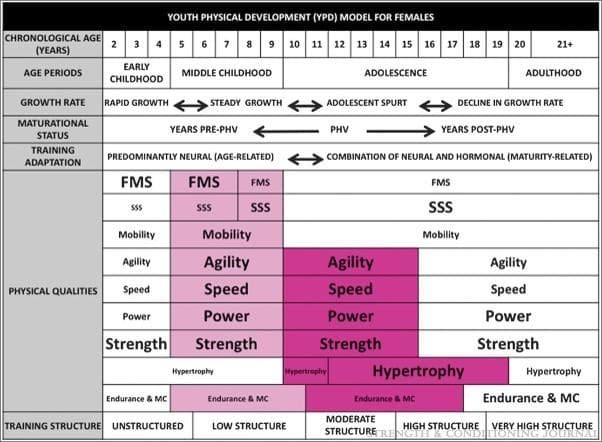

Lloyd and Oliver Youth Physical Development Model

Lloyd and Oliver’s Model of Youth Physical Development is based on these windows or sensitive periods when giving more importance to one quality or another. The authors emphasize that there is a pre-adolescent boost in strength, speed, explosive strength and endurance in both boys and girls (Viru et al., 2006). They also identified that there were spikes in speed and endurance before and around PHV (peak height growth velocity), respectively, while accelerated gains in strength qualities occurred after PHV. Based on all of this, they created the following two figures that we will look at in the following sections, one for boys and one for girls.

Windows of opportunity in children and adolescents for long-term athletic development

This is the model for children and teenagers. To understand what it means, you must take into account the following parameters:

- Font size refers to importance. When the letters are larger it is because you have to work more on that quality. When the letters are smaller it is better to give importance to another quality and give this one less training load.

- Light blue boxes refer to pre-adolescent adaptation periods, dark blue boxes refer to adolescent adaptation periods.

- FMS = fundamental movement skills; MC = metabolic conditioning; PHV = peak height velocity; SSS = sport-specific skills; YPD = youth physical development.

Image taken from (Lloyd & Oliver, 2012)

Looking closely at the table we can take the example of a 12- to 13-year-old child. At this age, he should primarily focus his training on strength, power, speed, agility and sport specific skill development (SSS), with a reduced focus on hypertrophy, mobility, fundamental movement skill (FMS), endurance and metabolic conditioning.

Windows of opportunity in girls and adolescents for long-term athletic development

This is the model for girls and adolescents. To understand what it means, you must take into account the following parameters:

- Font size refers to importance. When the letters are larger it is because you have to work more on that quality. When the letters are smaller it is better to give importance to another quality and give this one less training load.

- Light pink boxes refer to pre-adolescent adjustment periods, dark pink squares refer to adolescent adjustment periods.

- FMS = fundamental movement skills; MC = metabolic conditioning; PHV = peak height velocity; SSS = sport-specific skills; YPD = youth physical development.

Image taken from (Lloyd & Oliver, 2012)

Looking closely at the table we can take the example of a seven-year-old girl. At this age her training should have a high load of fundamental movement skills (FMS), as well as agility, speed, power and strength. Other qualities such as hypertrophy and endurance are less trainable, as well as others that are not yet as important as sport specific skills (SSS), which will gain training load as we advance in age.

Practical application of LTAD

Image taken from Vitolda Klein (Unsplash)

It is now time to see the practical application of all the above theory. Lloyd’s group has several investigations in which they expose which quality is more interesting to work on according to biological age (Lloyd & Oliver, 2012; Lloyd et al., 2015a, 2015b). As we already know, it is best to take biological maturation with parameters such as maximum height growth velocity or weight gain velocity. However, for guidance, Lloyd and colleagues set out general guidelines that can be followed by any coach working with children and considering their long-term athletic development.

Fundamental movement skills versus specific sports skills

One of the simplest guidelines to understand and apply is the load we place on fundamental movement skills (FMS) and their antonym, sport specific skills (SSS). In the early stages of physical literacy, we should focus training on FMS as the foundation for everything else. As we get older, these fundamental skills become less important, while sport-specific skills (SSS) take up more and more of the training (Lloyd et al., 2015b, 2015a).

In the following image extracted from (Balyi et al., 2016) the main sport skills can be seen. In the early stages of the long-term athletic development model all of them should be there. Quite the opposite happens when we are in the later stages of long-term athletic development, in which we will focus on that or those specific to our sport. This does not mean that we should abandon the other more generic movement skills. These should always be present, although in smaller proportions as we progress through adolescence.

Image taken from (Balyi et al., 2016)

Mobility: it is always there, but there is no critical period for it

The Lloyd and Oliver Model of Youth Physical Development intends that at no time should mobility be the primary emphasis of a training program during childhood or adolescence. However, it should be noted that the development and maintenance of mobility must be an essential part of any athletic program to ensure that athletes are able to achieve the ranges of motion required for their sports.

Middle childhood (ages 5 to 11 years) serves as the most important time frame for an individual to incorporate flexibility and mobility training. The rationale for this selection is that it incorporates a period that has previously been referred to as the critical developmental period for flexibility. Sex differences are evident within the research, suggesting that boys show a reduction in forward trunk flexibility between the ages of 9 and 12, while girls show accelerated improvement from the age of 11.

Agility and speed

Between the ages of 5 and 16 in boys, and 5 and 15 in girls, agility and speed have critical periods in which we must increase their importance. Of course, this training will be present in the adult stage, but if we take advantage of those windows of opportunity through played tasks in the early years, and increasingly specific tasks in the later years, we will have a very good base on which to work on the athlete in the future.

Strength, power and muscle hypertrophy

Children can safely and effectively participate in strength training when it is prescribed and supervised by properly trained personnel. If we look at the charts in Lloyd and Oliver’s Youth Physical Development Model, we will see that strength is always in big letters, i.e., it is important at any age. What we will change is the way to train it, but we will start training strength from the early stages of maturity.

- Girls from 6 to 8 years old and boys from 6 to 9 years old (FUNdamentals stage): games with body weight or small loads such as medicine balls. Without going too much into the perfect technique of execution, we will stop in that part in order not to create technical failures from the base.

- Girls from 9 to 11 years old and boys from 10 to 13 years old (learning to train stage): in addition to the previous strength exercises, we will include work with free weights mainly oriented to the technical execution of the exercises. Remember that the learning to train stage lays the foundation for future training. This phase also takes into account plyometric games in which the correct mechanics of jumping and landing are learned.

- Girls from 12 to 18 years old and boys from 14 to 18 years old (training to train stage): at this stage we are already in full growth in height and weight. Plyometric training increases the depth of jumping and falling. The loads go from light to moderate in strength training, and muscle hypertrophy work is included here, since we are in a critical period of muscle mass increase. It is also important to increase the use of eccentric training during this stage, as well as to focus strength training specifically on the sport in which we are going to specialize.

- Over 18 years of age (training to compete and to win): in the adult stage, we will train strength in a normal way, since here there are not those windows of opportunity that we have had throughout childhood and adolescence. In the previous stages we have learned to land correctly, so the plyometrics used can be with moderate and high heights. Technical exercises such as Olympic lifts have also had to be learned previously, so now we will be lifting more and more load, all focused on our sport.

Therefore, strength and power work will be present throughout the entire athletic development process. More hypertrophy-oriented work will become important a few years after the onset of puberty to take advantage of these physical changes of increased muscle mass.

The ideal way to monitor strength training in children and adolescents, as well as adults, is to have a device such as the Vitruve device that measures the speed at which we move or the speed at which the bar moves. In children and adolescents, we will not lift high weights, nor will we go to muscle failure, which means that, if we do not use this type of velocity measurement devices, we will be very blind about the load used and the progress that exists or does not exist. By measuring a vertical jump, or the speed at which we push a medium or low load, we will be able to control and prescribe loads much more accurately, especially in children and adolescents. The same is true for adults, which is why a velocity measurement device like Vitruve is essential for strength, power or hypertrophy training at any age.

Joaquin Vico Plaza

References

- Balyi, I., & Hamilton, A. (2004). Long-term athlete development: Trainability in childhood and adolescence. Olympic Coach, 16(1), 4–9.

- Balyi, I., Way, R., & Higgs, C. (2013). Long-term athlete development. Human Kinetics.

- Balyi, I., Way, R., Higgs, C., Norris, S., & Cardinal, C. (2016). Long-Term Athlete Development 2.1 Canadian Sport for Life.

- Dunton, G. F., Do, B., & Wang, S. D. (2020). Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-020-09429-3

- Ford, P., de Ste Croix, M., Lloyd, R., Meyers, R., Moosavi, M., Oliver, J., … Williams, C. (2011). The long-term athlete development model: physiological evidence and application. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(4), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.536849

- Granacher, U., & Borde, R. (2017). Effects of Sport-Specific Training during the Early Stages of Long-Term Athlete Development on Physical Fitness, Body Composition, Cognitive, and Academic Performances. Frontiers in Physiology, 8(OCT). https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2017.00810

- Granacher, U., Lesinski, M., Büsch, D., Muehlbauer, T., Prieske, O., Puta, C., … Behm, D. G. (2016). Effects of Resistance Training in Youth Athletes on Muscular Fitness and Athletic Performance: A Conceptual Model for Long-Term Athlete Development. Frontiers in Physiology, 7(MAY), 164. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2016.00164

- Lloyd, R. S., & Oliver, J. L. (2012). The youth physical development model: A new approach to long-term athletic development. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34(3), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0B013E31825760EA

- Lloyd, R. S., Oliver, J. L., Faigenbaum, A. D., Howard, R., De Ste Croix, M. B. A., Williams, C. A., … Myer, G. D. (2015a). Long-term athletic development- Part 1: A pathway for all youth. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(5), 1439–1450. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000756

- Lloyd, R. S., Oliver, J. L., Faigenbaum, A. D., Howard, R., De Ste Croix, M. B. A., Williams, C. A., … Myer, G. D. (2015b). Long-term athletic development, part 2: barriers to success and potential solutions. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(5), 1451–1464. https://doi.org/10.1519/01.JSC.0000465424.75389.56

- Myer, G. D., Jayanthi, N., Difiori, J. P., Faigenbaum, A. D., Kiefer, A. W., Logerstedt, D., & Micheli, L. J. (2015). Sport Specialization, Part I: Does Early Sports Specialization Increase Negative Outcomes and Reduce the Opportunity for Success in Young Athletes? Sports Health, 7(5), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738115598747

- Piercy, K. L., Troiano, R. P., Ballard, R. M., Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Galuska, D. A., … Olson, R. D. (2018). The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA, 320(19), 2020–2028. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2018.14854

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). The National Youth Sports Strategy.

- Varghese, M., Ruparell, S., & LaBella, C. (2022). Youth Athlete Development Models: A Narrative Review. Sports Health, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/19417381211055396

- Viru, A., Loko, J., Harro, M., Volver, A., Laaneots, L., & Viru, M. (2006). Critical Periods in the Development of Performance Capacity During Childhood and Adolescence. Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/1740898990040106, 4(1), 75–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898990040106

- Washington, R. L., Bernhardt, D. T., Gomez, J., Johnson, M. D., Martin, T. J., Rowland, T. W., … Li, S. (2001). Organized sports for children and preadolescents. Pediatrics, 107(6), 1459–1462. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.107.6.1459