28 de October de 2022

Types of Strength Training Periodization and Its Benefits

Differences between planning, periodization and scheduling

There are three terms that are often confused when we want to capture in a calendar the objectives of the training and the sessions that we are going to carry out to achieve it. Planning, periodization, and scheduling are often interchanged, but each term refers to different functions (Kataoka, Vasenina, Loenneke, & Buckner, 2021).

Planning

Planning consists of collecting the information of the subject, as well as his objective to be achieved in order to take him or to a calendar. In this planning phase, the needs of the athlete are evaluated to know who we are going to train, the type and number of objectives they have and the time we have to reach them. It is at this moment when the important competitions are planned, knowing that we will not be able to be at our maximum level of strength in all of them.

If you like football, you’ve probably heard phrases like “this team always has a physical slump in February ”. That physical slump can be part of the planning of the season that is done before the preseason. With the calendar in hand, we look for the moments in which we can intensify strength training, or when training will simply be based on recovering between matches. That will be done by periodization.

Periodization

We have already planned the goal and put it on a calendar. Now we have to organize the time we have until that goal. Periodization consists of determining the working blocks, but without specifying any type of variable such as volume, intensity, frequency, etc. (D. Lorenz & Morrison, 2015). In this phase we will study the moments when we can add more load and those when we will have to lower the intensity to recover.

We will also organize the periods of time that we are going to dedicate to a specific goal: muscle hypertrophy, strength, power, etc. Periodization is the management of these temporary structures throughout the season, chaining the blocks and training phases according to the objectives set (D. S. Lorenz, Reiman, & Walker, 2010).

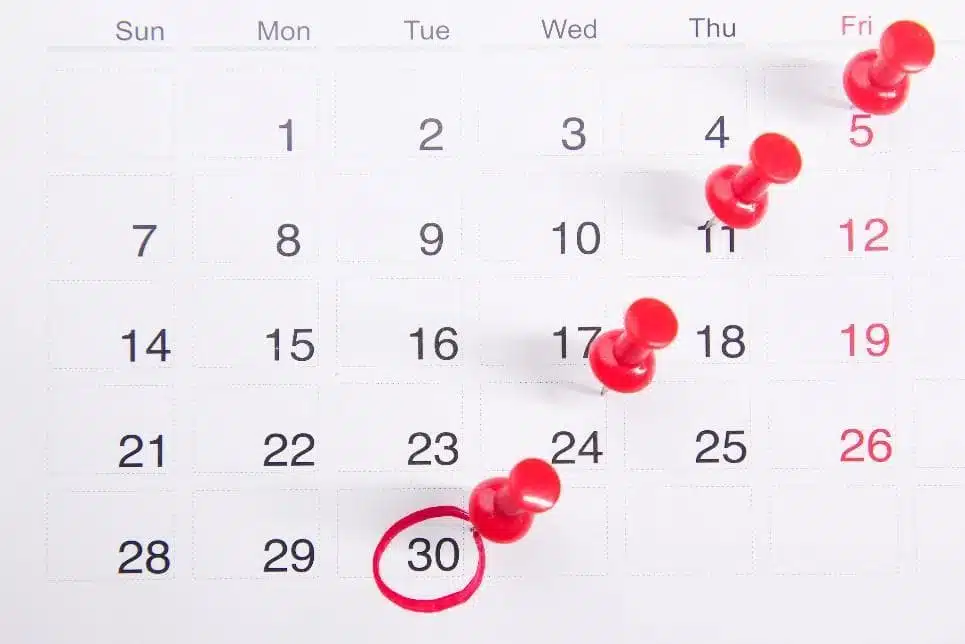

From longer to shorter duration, periodization is structured in a macrocycle that encompasses several mesocycles (Strohacker, Fazzino, Breslin, & Xu, 2015). Mesocycles are a set of microcycles. Microcycles have a set number of training sessions. The duration of the macrocycle can range from several months to a full Olympic cycle of several years. This macrocycle is the succession of several mesocycles looking for a peak of adaptation that will coincide with an important competition.

Mesocycles are the set of microcycles associated with a common goal. They usually couple between three and six microcycles. The microcycles have an average extension of seven days, taking advantage of the natural week, but can range from four days to 14, according to our preferences. Each microcycle consists of several training sessions, which are scheduled day by day (Haff & Triplett, 2016).

Programming

Scheduling is defining the training variables of each session, especially intensity and volume. Therefore, the programming consists of specifying the number of days we are going to train and what we are going to do each of those sessions. Depending on the programmed variables, we will have a microcycle (set of sessions) with a greater or lesser impact.

Some authors propose a last step that they call “prescription”. This part of the programming would be that final sheet that the athlete receives in each training to know what exercises he has to do, how many series, with what weight, etc. This is the smallest part of planning, which as we have seen depends on periodization and scheduling.

Types of periodization

We have just seen that periodization is a general concept that deals with dividing the training process into specific phases. Programming is the manipulation of variables within these phases. The doubt comes when we want to manipulate all those training variables over time to maximize strength adaptations, without falling short or overdoing it.

Matveyev in the mid-1960s began to delve deeper into sports periodization, as have other important authors such as Platonov, Issurin or Bompa (Lyakh, Mikołajec, Bujas, & Litkowycz, 2014). The common idea of all of them is that training should gradually modulate volume and intensity to generate stress peaks that make us improve strength, alternating stages of lower load to recover. There are currently three common models of training periodization (Evans, 2019).

Linear or classical periodization model

The linear periodization model is also known as the regular loads model, since there is a gradual increase in intensity as the volume progressively decreases (Mujika, Halson, Burke, Balagué, & Farrow, 2018). The closer we get to the competition or the moment of peak performance, the intensity will be maximum and the volume will be minimal. An example of linear periodization can be the following:

- A four-week mesocycle of hypertrophy gradually increased loads by 60% to 75%.

- A four-week mesocycle of maximum strength gradually increasing loads by 80% to 90%

- A three-week power mesocycle with a low volume and very high intensities.

- A tapering or microcycle of assimilation of all the above, which ends with the competition.

- Download or transition to a new macrocycle.

The linear periodization model can also be reversed, that is, it begins with a high intensity that gradually decreases as the volume increases (Evans, 2019). In strength it is not used since it is preferable to start with a high volume and low intensity and end with a high intensity and a low volume. However, in resistance it is more used as we accumulate more and more kilometers to prepare for a competition (Cardona, Cejuela, & Esteve, 2019).

Nonlinear or undulating periodization model

The nonlinear or undulating periodization model, as its name suggests, involves frequent load variations that can occur weekly or daily (Buford, Rossi, Smith, & Warren, 2007). If in the linear model the progress of the variables was much more monotonous and slow, here we can train in the same week with a day of moderate intensity aimed at muscle hypertrophy, a day of power with medium loads and very high speeds and another day with loads close to the maximum to work pure strength (D. Lorenz & Morrison, 2015).

Then we will see that this model is the most interesting, especially when it comes to improving strength in medium and advanced level athletes. An example to visualize this model that could be used in powerlifting is the one below. As you can see, each day of the week the volume and intensity vary:

- Day 1 (week 1): moderate intensity (70-75% of 1RM) with a medium range of 8 – 12 repetitions

- Day 2 (week 1): Power with 60% of 1RM and power exercises

- Day 3 (week 1): very high intensity (90-95% of 1RM) with a very low range of 1 to 3 repetitions

- Day 4 (week 2): moderate intensity such as day 1 of week 1

- Day 5 (week 2): gentle intensity (60% of 1RM) in a circuit of machines with medium – high repetitions

- Day 6 (week 2): high intensity (80-85%) doing 5 repetitions of basic exercises such as squat, bench press and weighted pull-ups.

Block periodization model

The block periodization model organizes the training loads in a concentrated way following a logical order so that the next phase takes advantage of the previous one. The ATR model is one of the most widely used and consists of three phases that form its acronym: Accumulation, Transformation and Realization (Stone et al., 2021).

The first phase, or first block, is accumulation used to work on the basics of each quality, whether strength, endurance or technique. The volumes are between high and high and high and the intensity is moderate. In this phase performance is compromised so it cannot be used near a competition.

The second block is transformation. It seeks to direct the profits obtained in the previous phase towards our sport. Here the volume is lower and the intensity is greater, but always with optimal rest. If our goal is to jump more for a mate in basketball or a shot in volleyball, in the first block we will have worked on basic exercises such as the squat, while in this phase we focus on jumps and plyometrics.

The third block of realization is to apply all the previous work in a specific competition situation. The intensity is maximum and the volume is minimal. In this phase we will work with different tasks: the jumps to the basket and the volleyball jumps, that is, we go to tasks of sport or competition.

Do any of the three periodization models stand out from the others?

The principle of overload is the basis on which the improvement of force is based. Moving the same load faster every time, lifting more kilos, doing more repetitions… It means that we have gained strength. Therefore, periodization is key to increasing muscle strength to a greater extent than if we do not have a periodization or logical order (Evans, 2019). However, the scientific literature shows contradictory results that do not allow reaching a consensus on which periodization model is better than another (Pitta et al., 2019).

Although there are such contradictory results, the trend is slightly towards the nonlinear or undulating periodization model. The linear periodization model may show worse results since the studies are usually of short duration, and being a slower model the strength gains may appear later (Monteiro et al., 2009).

There may also be variations according to the level of the strength athlete, since in beginners strength gains are observed in the three models evaluated (Buford et al., 2007). In this group of population beginners in strength, a linear periodization model is recommended since they first need to go through a process of anatomical adaptation and hypertrophy, before entering fully with maximum strength and power.

If we had to opt for a model of the three for intermediate or advanced athletes in strength, we would choose the nonlinear periodization model, undulating the volume and intensity daily. The strength gains obtained in several studies give it as a winning model (Prestes et al., 2009; Rhea, Ball, Phillips, & Burkett, 2002; Simão et al., 2012; Spineti et al., 2013), although as we have mentioned there are contradictory results due to the difficulty of equalizing all the training variables.

Benefits of periodization

Image extracted from https://unsplash.com/es/fotos/bwOAixLG0uc

Supercompensation instead of exhaustion

Our body adapts to stimuli, so if we always do the same thing we will stagnate very soon. This phenomenon is known as general adaptation syndrome and is the basic reason why periodization exists (Cunanan et al., 2018). If we exceed with training we can enter a picture of overtraining. That is why we need to alter the stimuli that our athlete receives, there are moments that will be of a high impact, followed by microcycles of discharge so that he can recover.

When the stimulus is very stressful we will see a drop in performance, but once we have passed that alarm phase there will be a supercompensation in which we will be stronger. Of course, if the highly stressful phase is excessive, exhaustion occurs. Here is the art of periodization, in achieving the balance between fitness and fatigue so that we maximize super compensations without stagnating or reaching exhaustion.

We reach peak performance when we care

One of the main benefits of periodization is that by modulating the different training variables over time we can match them when we are interested in being at the highest level. If we have an important powerlifting competition, we will periodize all the training around it. This is easier to do in sports where there are a few peaks of performance in the season, but it becomes more difficult in sports like basketball where we have to perform every week.

Variation against boredom and injury

The manipulation of the number of sets, repetitions, the weight lifted, the exercises, etc. makes us see a progression and not get bored in the process. If we do not carry out a periodization and train without a logical order, we will not know well what to do, we will get bored and we will abandon when we do not see advances in our strength gains.

Of course, controlling training variables through proper periodization and scheduling will reduce the risk of injury (Heard, Willcox, Falvo, Blatt, & Helmer, 2020). We will also be able to control the emotional stress that can occur with training, especially when we focus on an important competition. Such vigilance will also reduce the risk of injury in athletes, as an elevated level of emotional stress correlates with a high rate of injury (Ivarsson et al., 2017).

Joaquin Vico Plaza

References

Buford, T. W., Rossi, S. J., Smith, D. B., & Warren, A. J. (2007). A comparison of periodization models during nine weeks with equated volume and intensity for strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(4), 1245–1250. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-20446.1

Cardona, C., Cejuela, R., & Esteve, J. (2019). Manual for training endurance sports.

Cunanan, A. J., DeWeese, B. H., Wagle, J. P., Carroll, K. M., Sausaman, R., Hornsby, W. G., … Stone, M. H. (2018). The General Adaptation Syndrome: A Foundation for the Concept of Periodization. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) , 48(4), 787–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-017-0855-3

Evans, J. W. (2019). Periodized Resistance Training for Enhancing Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength: A Mini-Review. Frontiers in Physiology, 10(JAN). https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2019.00013

Haff, G., & Triplett, N. T. (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning, 735.

Heard, C., Willcox, M., Falvo, M., Blatt, M., & Helmer, D. (2020). Effects of Linear Periodization Training on Performance Gains and Injury Prevention in a Garrisoned Military Unit. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health, 28(3), 23. Retrieved from /pmc/articles/PMC7590922/

Ivarsson, A., Johnson, U., Andersen, M. B., Tranaeus, U., Stenling, A., & Lindwall, M. (2017). Psychosocial Factors and Sport Injuries: Meta-analyses for Prediction and Prevention. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) , 47(2), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-016-0578-X

Kataoka, R., Vasenina, E., Loenneke, J., & Buckner, S. L. (2021). Periodization: Variation in the Definition and Discrepancies in Study Design. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) , 51(4), 625–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-020-01414-5

Lorenz, D., & Morrison, S. (2015). CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIODIZATION OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR THE SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPIST. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 10(6), 734. Retrieved from /pmc/articles/PMC4637911/

Lorenz, D. S., Reiman, M. P., & Walker, J. C. (2010). Periodization: current review and suggested implementation for athletic rehabilitation. Sports Health, 2(6), 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738110375910

Lyakh, V., Mikołajec, K., Bujas, P., & Litkowycz, R. (2014). Review of Platonov’s “Sports Training Periodization. General Theory and its Practical Application” – Kiev: Olympic Literature, 2013. Journal of Human Kinetics, 44(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.2478/HUKIN-2014-0131

Monteiro, A. G., Aoki, M. S., Evangelista, A. L., Alveno, D. A., Monteiro, G. A., Piçarro, I. D. C., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2009). Nonlinear periodization maximizes strength gains in split resistance training routines. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(4), 1321–1326. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181A00F96

Mujika, I., Halson, S., Burke, L. M., Balagué, G., & Farrow, D. (2018). An Integrated, Multifactorial Approach to Periodization for Optimal Performance in Individual and Team Sports. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 13(5), 538–561. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSPP.2018-0093

Pitta, R., Montenegro, C. P., Rica, R., Bocalini, D., Tibana, R., Prestes, J., … Jr., A. F. (2019). Comparison of the Effects of Linear and Non-Linear Resistance Training Periodization on Morphofunctional Capacity of Subjects with Different Fitness Levels: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Exercise Science, 12(4). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijes/vol12/iss4/10

Prestes, J., Frollini, A. B., de Lima, C., Donatto, F. F., Foschini, D., de Cássia Marqueti, R., … Fleck, S. J. (2009). Comparison between linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training to increase strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(9), 2437–2442. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181C03548

Rhea, M. R., Ball, S. D., Phillips, W. T., & Burkett, L. N. (2002). A Comparison of Linear and Daily Undulating Periodized Programs with Equated Volume and Intensity for Strength. National Strength & Conditioning Association J. Strength Cond. Res, 16(2), 250–255.

Simão, R., Spineti, J., De Salles, B. F., Matta, T., Fernandes, L., Fleck, S. J., … Strom-Olsen, H. E. (2012). Comparison between nonlinear and linear periodized resistance training: hypertrophic and strength effects. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(5), 1389–1395. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318231A659

Spineti, J., Figueiredo, T., de Salles, B. F., Assis, M., Fernandes, L., Novaes, J., & Simão, R. (2013). Comparison between different periodization models on muscular strength and thickness in a muscle group increasing sequence. Revista Brasileira de Medicina Do Esporte, 19(4), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-86922013000400011

Stone, M. H., Hornsby, W. G., Haff, G. G., Fry, A. C., Suarez, D. G., Liu, J., … Pierce, K. C. (2021). Periodization and Block Periodization in Sports: Emphasis on Strength-Power Training-A Provocative and Challenging Narrative. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(8), 2351–2371. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004050

Strohacker, K., Fazzino, D., Breslin, W. L., & Xu, X. (2015). The use of periodization in exercise prescriptions for inactive adults: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2, 385. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PMEDR.2015.04.023