27 de March de 2023

Transfer of Training During Strength Exercises

What Does Transfer Training Means?

The concept of “training transfer” is a hot topic in discussions among strength and conditioning coaches. This term refers to the degree to which a workout affects a particular performance or task (Issurin, 2013). For example, is performing power loads in the gym going to improve our 100m sprint performance? If the answer to that question is yes, then there will a be transfer of that strength training to our sport. If the training does not improve our sport performance, there will be no transfer.

It is the transfer of training that ultimately determines the effectiveness of the strength training program. In this article, we are addressing the transfer of strength training to improvements in sports performance and competition. To do so, we have used a high-quality article by Brearley and Bishop as our primary source, in which they thoroughly detail training transfer (Brearley & Bishop, 2019).

Stages of Training Transfer

In the early stages of training, as is the case in preseason in many sports, physical sessions can be far removed from discipline-specific and discipline-specific movements (Haff, 2004). As the athlete approaches competition stages, the goal is that all that work done becomes a better athletic performance (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007). Several authors have proposed different models of sports periodization to delimit training categories according to their exercises and the specificity of the exercises in relation to the ultimate goal: the needs of the sport (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007; Bosch, 2015; Issurin, 2013; Verkhoshansky & Siff, 2009).

It is important to highlight and understand the concept of specificity, as the principle that describes the specific effect of training on the sport’s own gestures. This specificity can be global (speed, amplitude, movement, etc.) or local (muscular activity, force rate, etc.). The training transfer models that follow show that it is not feasible to design a task that meets all the needs of a sport, but it is possible to focus on one or two aspects of the sport-specific gesture where training transfer is applicable.

Issurin: Strength Transfer vs. Skill Transfer

If you want to learn to play the piano (skill), you have to play the piano. Performing finger agility exercises (ability) can help in that task, but it will be of little use if we do not spend hours and hours developing the technical skill (playing the piano). Issurin, like other authors, suggests that strength training, even if somewhat more generalized, has the potential to produce a transfer effect (Issurin, 2013; Zatsiorsky, Kraemer, & Fry, 2020). However, technical skill development requires specific practice to be effective.

This discrepancy between the improvement of technical skills and the transfer of strength with more specific or general training, is the cause of finding authors who defend the need for specificity in the transfer of strength, while others believe that it is not necessary so much specificity and more generic exercises and phases are sufficient (Brearley & Bishop, 2019). They say that there is virtue in balance, so the ideal is to move away from both specific and general extremes, or in other words, to use the entire continuum in between. To this end, we will now look at Bondarchuk’s four categories, which we will fill in with selected exercises according to Siff’s and Verkhoshansky’s laws, as well as Bosch’s extra features.

Exercise Characteristics That Produce a Suitable Transfer in Training

Siff & Verkhoshansky’s Five Laws of Dynamic Correspondence

Siff and Verkhoshansky established already three decades ago their five laws of dynamic correspondence, which is totally linked to the transfer of training (Verkhoshansky & Siff, 2009). The authors propose that we classify exercises into a more general or more specific phase according to these five criteria:

- Amplitude and direction of movement

- Accentuated region of force production

- Dynamics of the effort

- Rate and time of maximal force production

- Muscle work regime

The more an exercise resembles the sporting gesture in these five characteristics, the more specific it will be. The transfer of training will depend on choosing the right exercises at the right time. For example, horizontal run involves different muscle groups of the lower body. Hip thrust will more closely resemble the demands of such a horizontal displacement than a squat, because the direction of the movement, the muscles involved and the force is applied in a more similar fashion. However, in a vertical jump it will be more interesting to perform squats rather than hip thrust for the same reason.

The idea for a successful transfer of strength is that, to a greater or lesser degree of specificity, the exercises performed in training are focused on a specific objective (Young, 2006). The biggest mistake a strength and conditioning coach makes is to waste time and energy on exercises that will not produce a transfer from training to competition. That is why it is so important to know the specificity of each sport, and to control the general and specific exercises to improve them.

Bosch’s Three Categories of Specificity

Bosch provided a systematic division of the exercises that, in combination with clear intention, makes it easy to navigate within the central / peripheral model and links up key aspects of training.

- Intramuscular and intermuscular coordination: the external movement of the joints and the production of energy must resemble the sporting gesture.

- Sensory input: the arrival of external information, as well as that of the body itself (proprioception) must resemble the sporting gesture for the transfer of training to be effective.

- Similarity of intention: a 100m sprinter will focus only on running to the finish line as fast as possible, but a soccer player running away from the defense must run as fast as possible while keeping an eye on more factors. When it comes to training, aspects like this must be taken into account because, if the soccer player gets used to doing sled dragging drills without having external stimuli, the transfer may not be complete afterwards. In the same way, dragging a sled with a certain load increases the contact time with the ground and our goal with athletes is to make those supports as fast as possible.

Bondarchuk’s Four Exercise Categories

Bondarchuk developed an exercise classification system consisting of four categories almost four decades ago (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007). Each of them is used to introduce different exercises according to the degree of similarity with the gestures of competition. There are authors who give more importance to some exercises or others, while most of them decide for a mixed development of all of them. In this section we only list them, but we will shape them throughout the article with all the information seen so far.

- General Preparatory Exercises (GPEs)

- Specific Preparatory Exercises (SPE)

- Specialized developmental exercises (SDE).

- Competitive exercises (CE)

Extracted from Sven Kucinic (Unsplash)

Aims Analysis & Exercise Creation With The Ideal Transfer From Training To Competition

Knowing if an exercise is more or less specific we will have check back at each of Siff Verkhoshansky’s five laws, as well as Bosch’s three extra layers. Once it is classified according to its level of similarity with one or more gestures of our sport discipline, we can place it in one of Bondarchuk’s four phases. This way, we will start training with more general exercises that focus on strength development, but not so much on specific technical skills, and we will progress until that is reversed, focusing on technical skills with strength development specific at competition.

It will be at that point, where the transfer of strength training which has been done in the previous phases will take place. For example, if we want to improve our sprinting, we will start with a clean in the most general phase. We will continue with a heavy sled drag in the next, more specific phase. In the third phase, being more specialized already, we can introduce medicine ball throws with horizontal displacement. The fourth and last phase will be dedicated to the sprint gestures, with very little or no variation, such as a short sprint with a slight incline, or a resisted sled sprint with very little load.

Specific Sport Requirements: The First Thing Should Consider When it Comes to Training Transfer

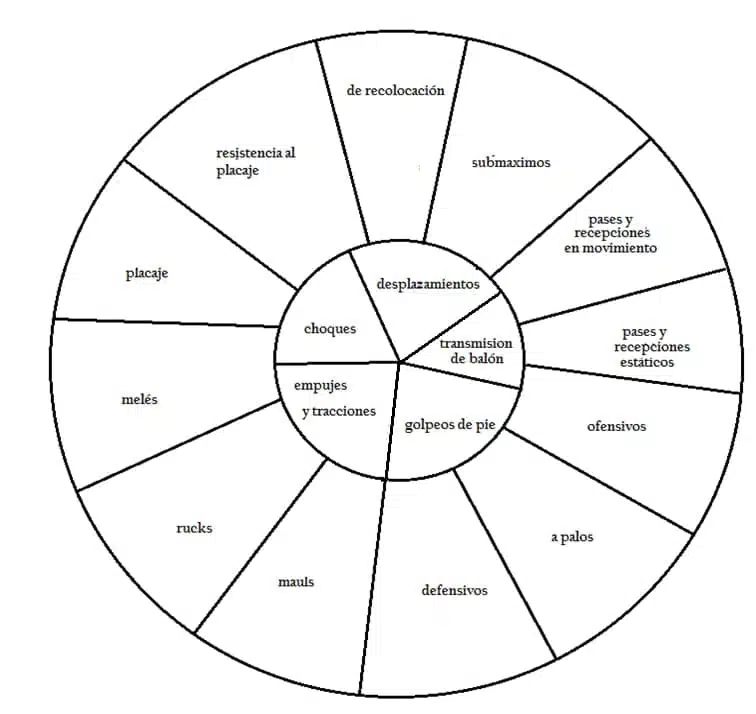

Each sport has its own requirements, so it is not possible to establish exercises that have an effective transfer of training to all of them. In turn, each sport has different areas and contents to train, so each of them needs its own exercises and phases. Rugby, for example, has several areas: displacements, collisions, pushes and tractions, foot strikes and ball transmission (Fernández-Valdes, 2020).

Each of these areas has different content to work on. Resistance to tackling in rugby, either avoiding the collision or colliding without being tackled, is one of the contents to work on. There are many others, depending on the area we want to improve. The following image shows the different areas and contents to work on in rugby. To do this in your sport you will have to analyze what your needs are and establish the areas and contents. Based on them, as we will see later, exercises and tasks will be proposed whose ultimate goal is that all this work is transferred to the competition.

From now on, we will be using Rugby as an example. There are specific contents that determine the differences in winning or losing a match. In Rugby, tackling is an action that is repeated over and over again, and that has different requirements depending on whether we are the player carrying the ball or if we are the defender tackling the player carrying the ball. The strength training will be different for one or the other. In our example we are going to assume that a specific objective we want to improve is the defense of the ball carrier to avoid being tackled.

That’s just one of the specific objectives, but there are many more in relation to all the actions of the game: melees, rucks, hitting the sticks, passing and receiving the ball, changes of direction, etc. Therefore, the transfer of the strength training we do must conclude with an improvement of the player carrying the ball to succeed and avoid the tackle. Once that goal is set, we begin to include drills in each of the four phases established by Bondarchuk, depending on how far or close we are to the specificity of our goal.

This final objective, as an example, will be a side step (or swerve) + hand off, for which we need to work on displacement and shock. Once the objective is clear, we start working with general and specific exercises, so that everything we do has a training transfer towards that final objective.

General Preparatory Exercises (GPEs)

In this case, it doesn’t matter how specific or general the exercise is, but it must prepare the system so that, as we approach competitive exercises, the transfer of training is as maximum as possible. In this general phase, the basic strength exercises that will later be useful in our sporting discipline are performed. For example, squats with high weights can have a positive effect on jumping higher for a dunk in basketball or a slam dunk in volleyball.

Tasks at this stage are designed to develop skills but have very little impact on the specific competition task (technique). In our particular objective as an example (side step (or swerve) + hand off), we need to improve pushing strength as the player puts his arm out and pushes his defender. There is no doubt that the bench press will be a general exercise in which we need to gain maximal strength, which will then be transferred to this situation. We will also need to improve the maximal strength of the lower body to help us accelerate and get away from the defender. Exercises such as lateral lunges, squats or Olympic movements will be effective and the basis of strength that will then be transferred to that acceleration and change of direction.

Specific Preparatory Exercises (SPE)

The exercises performed are focused on improving the local muscular structure, but they do not necessarily have to resemble the final objective. For example, we can train the rotational strength of our trunk with specific exercises to refine more in the following phases and get a more powerful swing in golf or give a greater speed to the bat in baseball. In these exercises we tune a little more in the direction of our ultimate goal but we still don’t focus much on technical skill.

Continuing with our example to improve tackling endurance with a change of direction and thrust, there are drills intended for that purpose. One of them will be to perform the bench press, now with less weight and with greater acceleration. A bench press on a guided machine where we throw the bar would be an example that fits into this group of specific preparatory exercises. To take care of the displacement and change of direction, we can perform exercises such as single Leg Hang Clean to Box, which will give us applied force to move and accelerate faster in that impact of the foot with the ground.

Specialized Development Exercises (SDE)

In this group we can find the “sport specific exercises”, setting one or two aspects of the target task and training for them. The level of muscular recruitment should be similar to that which we will have in the sporting gestures of competition. We are getting closer to the technical ability of the sport itself, but the load is still present to a greater or lesser extent.

An example of exercises of this group for our rugby player would be to perform lateral jumps between hoops, even adding a vest with some ballast, in order to improve the final step we take when making a change of direction. The transfer of the training can be seen when a rugby player, or also an American soccer player, gets away from his defender making that change of direction that we have trained. Regarding the push with the free arm, we will ask the player to stand near a punching bag and move it at maximum speed. If it is feasible, we can even combine both tasks into one to make it more and more similar to the specific gesture to which we want to dedicate the transfer of training.

Competitive Exercises (CE)

In this group, tasks are performed identical to the competition or with a very small variation. An example of these competitive exercises can be to perform volleyball blocks with a light weighted medicine ball. The players jump to block an opposing shot, which will be a thrown medicine ball that they will have to block. We are working specifically on blocking but applying a light strength component.

In our rugby / Football player we will perform situations typical of the competition as a one on one, in which the defender will go to tackle and the player with the ball will focus on avoiding it with the side step (or swerve) + hand off that we have been working with all the exercises mentioned above. Just as we have been following a bottle funnel for this technical skill, we will do the same with all the others. In the general phase the exercises can be used for several final objectives, but the more specific exercises will be focused on improving one or two specific skills. That’s the way strength training transfer works to be successful for an athlete.

¿Does Transfer in Training Really Exist?

The transfer from training to competition clearly exists. The problem is that the integration of tasks for such transfer to occur is not always correct. It also greatly affects the level of the athlete, as an elite athlete already has very high physical capabilities that have less room for improvement (Issurin, 2013). The lack of understanding of many athletes about training transfer, as well as the impossibility of measuring such transfer in most occasions, cause that debate about the effectiveness or not of some exercises in training transfer (Burnie et al., 2017).

There are sports in which training effects are clearly observed. Track and field in general evaluates an athlete by how fast they run, how far they throw, or how far they are able to jump. If there is an improvement it is due to technical improvement or training. However, many sports are more technical than physical, as well as involving tactical elements. Putting it all together makes it more complex to measure the transfer of training that has occurred with training.

A VBT Device That Measures All That Can be Measured!

Virtruve’s speed measurement device allows us to track variables such as power and speed in a jump or in a bar. Having these variables under control, we will be able to control what we can measure. It is a matter of assessing whether the athlete is now stronger than before in certain movements. Continuing with the example that has accompanied us in this article, our rugby player will be able to apply more or less force on the ground when taking that step that makes him change direction to get away from the defender. He will also be able to exert more or less thrust force to move the opponent and avoid being tackled.

Both qualities can be measured with the speed measuring device. If he improves his power in changing direction and pushing with his arm, the evidence tells us that he will be more likely to avoid a tackle. That’s why the first thing we need to do is to know each of the needs of our sport and separate them into general and specific drills against which we can measure progress. If there has been a significant improvement in strength, speed and power in those exercises, the transfer from training to competition should be observable, at least that’s what the theory says (Brearley & Bishop, 2019).

Joaquín Vico Plaza

Bibliographical References

Bondarchuk, A., & Yessis, M. (2007). Transfer of training in sports. Ultimate Athlete Concepts, Mitchigan USA, 218.

Bosch, F. (2015). Strength training and coordination: an integrative approach.

Brearley, S., & Bishop, C. (2019). Transfer of training: How specific should we be? Strength and Conditioning Journal, 41(3), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000450

Burnie, L., Barratt, P., David’s, K., Stone, J., Worsfold, P., & Wheat, J. (2017). Coaches’ philosophies on the transfer of strength training to elite sports performance. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/1747954117747131, 13(5), 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117747131

Fernández-Valdes, B. (2020). Movement variability in resistance training in team sports.

Haff, G. (2004). Roundtable Discussion: Periodization of Training—Part 1. Strength and Conditioning Journal. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/29515078/Roundtable_Discussion_Periodization_of_Training_Part_1

Issurin, V. B. (2013). Training transfer: scientific background and insights for practical application. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 43(8), 675–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-013-0049-6

Verkhoshansky, Y., & Siff, M. C. (2009). Supertraining. Verkhoshansky SSTM Rome.

Young, W. B. (2006). Transfer of strength and power training to sports performance. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 1(2), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSPP.1.2.74

Zatsiorsky, V. M., Kraemer, W. J., & Fry, A. C. (2020). Science and practice of strength training. Human Kinetics.