17 de November de 2020

Strength and science Velocity Based Training

The Importance of Bridging the Gap Between Sports Science and Coaching

My name is Jason Tremblay. I’m a 28-year-old Strength & Conditioning professional, Sports Science template designer for the Calgary Flames, and business owner of The Strength Guys Inc., with a bachelor’s degree in Health & Physical Education as well as the Personal Fitness Trainer Certificate from Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta. During the first nine years of my career, I’ve been fortunate to coach the 2019 Best Lifter in the IPF, 3 IPF World Champions, 4 Continental Champions, 4 University World Cup Champions, and 18 National Champions in IPF affiliated organizations. I’ve also been privileged to learn from some of the brightest minds in strength & conditioning as mentors, including Carlo Buzzichelli, Brett Bartholomew, Natalie Kollars, Dan Noble, Ben Esgro, Matt Gary, Eric Helms, Alan Selby, and Ryan van Asten, as well as our staff members here at TSG.

I’m appreciative of Vitruve for their support of The Strength Guys coaches and athletes, including my colleagues Alfred Jong and Nicola Paviglianiti, and TSG athlete and Canada’s Best Lifter of 2020, Ben Langley. All of them will be writing here in the Vitruve blog in the coming weeks and months.

Studies

My career path isn’t the typical path of a Strength & Conditioning professional. I didn’t start out coaching with a background as a high-level competitive athlete. Instead, I was a 16-year-old overweight kid dealing with depression that used training to turn my health around and provide me with a sense of professional direction when I needed it most. Powerlifting coaching and The Strength Guys came to me, and I ended up coaching Taylor Atwood to his first USAPL National Championship back in 2014 before I had ever competed myself.

I’m also not writing to you today as someone who has “made it” yet as a Sports Scientist. Like all of the excellent young coaches in Strength & Conditioning and Strength Sports today, I’m still working to improve my craft and find better performance solutions for people from all walks of life who entrust their health and performance goals with me. So why do I feel qualified to write about Bridging the Gap Between Sports Science and Coaching? It’s because this is my path. I’ve had to lean on mentorship to learn about many of the soft skills and lessons that only coaching or athletic experiences can teach. With that said, I’ve also had to leverage my skill set as a creative, innovative, and organized person to carve out a path for my athletes and employees to succeed and to show that I belong and have value in high-performance settings.

What I’ve realized is that a common set of issues seems to exist amongst coaches. With the advancements in sports science research, methods, and equipment availability, coaches now have access to more data on their clientele than possible decades ago. A classic example of how sports science has progressed is here on the Vitruve page. Now you can access linear position transducer technology to conduct Velocity-Based Training for thousands of dollars less compared to the available technology from many years ago. Together, strength sports and strength & conditioning are moving away from the qualitative and towards more quantitative methods in how we prescribe training and describe performance.

Tips and experience

A simple tip that can make data analysis more insightful, enhance efficiency, and improve science communication to athletes is start documenting. One of the first and most important lessons I learned during numerous strength & conditioning internships was the standards of documentation required by the great coaches who I’ve worked with. This lesson was only further cemented and built upon by the standard of information kept by the Calgary Flames Strength & Conditioning Department. The difference between private sector S&C and professional team S&C is integration. The Flames S&C team is integrated into a network that communicates to Athletic & Physical Therapy and the coaching staff about the players’ performance level. These are conversations that can’t be had consistently without documenting player performance and injury.

What I took away from this experience back to my practice in the private sector is that I should document health and performance information. In doing so, I’ll have the ability to facilitate data-based conversations with other professionals in the athlete’s network, such as assistant coaches, nutrition professionals, sports psychologists, or physical therapists. These conversations have led to fruitful discussions on what may be contributing to the progress or lack of progress for an athlete most, when the nutrition plan of an athlete should be adjusted for different objectives, and what load management variables may have contributed to a complaint or injury – and it’s also improved our professionalism because we have our own form of health records on the athlete for future reference.What should you document? The most straightforward answer is any information that is helpful to you. Here are examples of how we maintain records of athlete health, assessments, and competition results.

Injury Documentation

- Health Status (Active, Inactive, Physical Complaint – Partial, Full, or No Time Missed)

- Bodyweight

- Date of Occurrence

- Body Part

- Type (Illness, Bone, Cartilage, Joint, Muscle, Tendon, etc.)

- Brief Description of Occurrence & Symptoms

Assessments

- Load

- Repetitions Performed

- Last Rep RPE

- Last Rep Velocity

- e1RM Change

- New e1RM

Competition

- Meet Title

- Category

- Division

- Bodyweight

- Placing

- Squat Attempts & Outcome

- Bench Press Attempts & Outcome

- Deadlift Attempts & Outcome

- Performance Notes (What were the key performance inhibitors for this competition? What went well for this competition?)

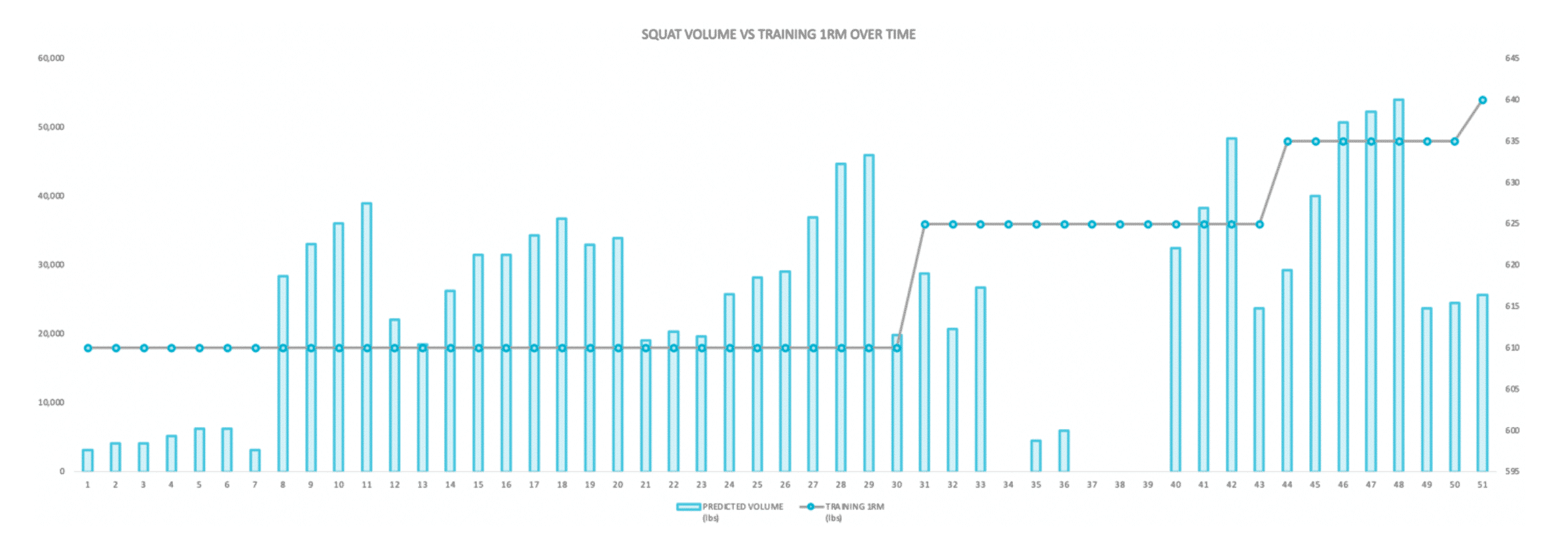

How a coach chooses to document performance doesn’t have to be fancy. We store this information in a simple Excel table, with each section corresponding to the same row as the training data from that week.A second tip that can improve a coach’s program’s quality is to start measuring and comparing your training interventions against the primary performance variable. For data-based decisions to occur, I think that a descriptive metric of the plan (i.e., training volume, training intensity, training frequency) and a performance variable (i.e., e1RM) should be tracked, compared, and visualized together. This form of analysis can highlight the correlation or lack thereof between the training workload and the outcome.Take a look at the correlation between weekly volume (Y-Axis on the left) and e1RM (Y-Axis on the right) of IPF World Champion & Best Lifter Taylor Atwood. Taylor won his 2nd World Championship and first Best Lifter award during Week 33 of this training year. We (his coaching team) can see a link between the high volume and tapering period from Week 27-30 and the increase in e1RM made in Week 30. What inferences did we make from this? The amount of volume that we performed at a high intensity near the competition helped him to progress.Another example within this same graph is in Weeks 40-48. Following the World Championship, we allowed Taylor to enjoy a vacation without the stressors of training. We quickly had to increase the training load again to prepare for Raw Nationals in Week 51. Using a similar approach to what had worked in preparation for the IPF World Championship months before, we saw Taylor’s performance increase to new heights. This all-time high level of training volume and intensity also exposed a weakness in the hips’ stabilizing muscles, which led to an injury sustained two weeks out from the competition. The load management inferences that we made from this are that the increase in loading may have been too much, too soon. Moving forward, we decided that similar increases in loading ought to be preceded by a lower intensity and higher volume period of training. This preparatory training period could improve load tolerance and work capacity and tap into the possible protective effect of maintaining a high chronic training load.

These are two examples of looking at a straightforward graph of weekly volume and estimated 1RM and making inferences on what improves performance and increases injury risk. This form of analysis is critical for bridging the gap between sports science (measuring, monitoring and documenting) and coaching (planning, implementing, teaching, inspiring, and holding athletes accountable).

A third simple tip to bridge the gap between sports science and coaching is to conduct data-based assessments. Much like a teacher wouldn’t wait until the final exam to evaluate his/her students’ level of understanding, a coach shouldn’t wait until the goal competition to attempt to understand the athlete’s performance level. Assessments are like tests in school; they allow us to understand better if the athlete is achieving the desired training stimulus. If assessments show the training is working, the coach can confirm that the training strategy is effective. If assessments show that the training is not working, the coach can make the necessary adjustments to the plan to make it progressive. Here are examples of the different assessment categories which our group may use.

Daily

– Monitor the mean concentric velocity of the main exercises.

– Monitor velocity-calculated e1RM of main exercises.

Weekly

– Perform a load-velocity profiling test for the specific warm-up.

– Work up to a peak intensity set and measure it with RPE or mean concentric velocity.

Monthly/Situational

– Direct 1RM test.

– Perform an AMRAP (as many reps as possible) strength evaluation with a cap of 2 reps above the RM.

Creating a historical record of these assessment results allows us to describe how an athlete’s performances have changed over time and helps make future interventions in the training plan.

The fourth and final tip for this blog is to create a data-based training system that contains the components discussed in this blog. Striving to create a system that revolves around documentation, data analysis, and assessments can help bridge the gap between sports science and coaching and provide the coach with new perspectives, strategies, and hopefully, newfound performance and health results for the athletes we train.