10 de November de 2023

How many times a week do powerlifters train?

Relationship Between Session Intensity and Training Days per Week in Powerlifting

Powerlifting is a sport of both relative and absolute maximum strength, comprising three movements: squat, bench press, and deadlift (Ferland & Comtois, 2019). This athletic discipline has existed as a strength sport for several decades but has gained increased attention in the last 10 to 15 years. In competition, a weightlifter has three attempts at a single repetition in each of the weightlifting exercises with the aim of achieving the highest total weight possible (Helms et al., 2017). The powerlifting total is calculated by adding the heaviest successful attempt in each of the three lifts.

As performance in powerlifting began to receive more attention from the strength and conditioning community, it became necessary to optimize training methods to enhance such performance. Answering questions like “how many times a week do powerlifters train?” is highly complex as world records have been achieved by training three days a week and also training six days a week. Each athlete follows a tailored training schedule based on their preferences, utilizing either high volume with submaximal loads or much lower volume with almost maximal loads.

When intensity varies, volume must also vary, and consequently, so do the training days per week. A common approach for preparing for a powerlifting competition involves varying volume and intensity throughout the season, employing progressive variations over time (linear periodization) or more abrupt changes within the week and even in the same session (undulating periodization). Regardless of the periodization model used, powerlifters incorporate both high and low training volumes, as well as high and low training loads when preparing for a competition (Androulakis-Korakakis et al., 2018).

One study that illustrates the lack of a general answer to the question “how many times a week do powerlifters train?” is that of Zourdos and colleagues (Zourdos et al., 2015), who examined the effect of performing squats every day for a period of 37 consecutive days. These researchers found that one-repetition maximum (1RM) strength improved after performing the following workout every day for those 37 days: a 1RM followed by 5 sets of 3 repetitions at 85% of 1RM or 2 repetitions at 90% of 1RM. There was no rest day during those 37 days. On the flip side, there are widely adopted powerlifting programs that base their schedules on training three or four days a week, as each day is much more demanding. The difference in session intensity will be the factor that answers the question “how many times a week do powerlifters train?

Analogy of the Wine Bottle and Training Days in Powerlifting

Before delving into data on the different practices of powerlifting competitors presented in scientific literature, let’s “open a bottle of wine.” In weightlifters, whether in powerlifting or for any other goal, the same question often arises: “How many times a week is it best to train?” The answer is also quite common: it depends on the intensity of each session, as that will determine the time we need to rest until the next training session.

Imagine I give you a bottle of wine and tell you that you have seven days to drink it. From that moment, you could decide to consume the entire bottle at once, split it into two halves on different days, or take a sip of wine three times a day, for example. Any option is good because what matters is that the wine bottle is empty after those seven days. What difference will it make whether you drink the bottle in one hour or distribute the wine over seven days, having a glass of wine each day? Correct, the hangover. That hangover is to wine what recovery is to training.

A powerlifter might come in on a Monday and do 14 sets of heavy lifting, or do two heavy sets every day of the week, resulting in the same number of sets. In both scenarios, we are doing “the same” training, but “the hangover” will be minimal, even nonexistent if we distribute the work throughout the week. If we do 14 sets on the same day (drink the bottle all at once), we’ll need much more recovery time to overcome that “hangover” or fatigue.

This analogy is crucial to understand the answer to the question “how many times a week do powerlifters train?” is answered with a “it depends on what they do each day.” A powerlifter can train seven days a week, and another four, and both options are valid. It will depend on their preferences and how well they manage fatigue, a factor that will determine whether we train more or fewer days. What we cannot do is train every day of the week with very high intensity, just as it is not advisable to train four days with low intensity. In the distribution of intensity and fatigue (of wine and hangover) lies the key to understanding why there is no magic number of days for powerlifting training.

How Many Times a Week Do Powerlifters Train? This is What Scientific Literature Says

Once we understand, through the analogy of the wine bottle, why there are powerlifting programs that train three or four days a week and others that train every day, we can take a look at various scientific publications that have analyzed the practices of expert powerlifters. One high-quality study accessible in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research explores the contemporary training practices of Norwegian weightlifters (Shaw et al., 2022). One hundred seventeen powerlifters, including world, European, and Norwegian champions, answered questions such as “how many times a week do powerlifters train?”

Thanks to the questionnaire they filled out, it was revealed that nearly 60% of Norwegian powerlifters trained 5-6 days a week, primarily using a load of 71-80% of 1RM. This indicates that Norwegian powerlifters train with high frequency (5 or more times per week), some even with double daily sessions, and with submaximal loads (Shaw et al., 2022). This practice differs significantly from classical recommendations, where training with much lower frequency was common. In Norway, powerlifters used to train only three days a week, performing the basic powerlifting movements once or twice a week.

Around the year 2000, Dietmar Wolf was appointed the national powerlifting coach in Norway, and “The Frequency Project” was implemented. This German coach applied the high-frequency method used in Olympic lifting to powerlifting. As a result, transitioning from three training sessions per week, classic training, to six sessions per week, contemporary training, led to a radical increase in performance and marks in squat, bench press, and deadlift (Saric et al., 2019). Despite knowing about these potential improvements when training more days a week, there are powerlifters, though increasingly fewer, who still follow the classical recommendations of 3-4 days of training per week, arguing that if the total weekly volume is equalized, there are no significant differences in strength gains (Colquhoun et al., 2018; Hillerström & Brandin, 2023). However, an increase in frequency favors an increase in volume and/or intensity, and that does increase the potential for gaining muscle strength (Heaselgrave et al., 2019).

Classic powerlifters like Arthur Saxon, Herman Gorner, and George Hackenschmidt trained an average of three or four days a week and achieved astonishing results for their time. On the other end was Paul Anderson, who trained squats a minimum of four days a week, sometimes doing squats daily, spreading the sets throughout the day. Do you remember the analogy of the wine bottle? With Paul Anderson, we have a clear example of that analogy by spreading his total volume of squats throughout the week and days.

High Frequency with Low Intensity versus Low Frequency with High Intensity

Currently, and always citing average figures, a beginner powerlifter can train three days a week on non-consecutive days; an intermediate powerlifter will increase by one or two days a week, training four or five times; and an advanced powerlifter typically trains five or six days a week. These figures are merely indicative and on average because more than the number of days per week, what we need to control is the intensity of each training session, which will determine the need for hours or days of rest, resulting in the total number of sessions per week.

This is where the choice between high-frequency training with low intensity per session versus low-frequency training with high intensity per session comes into play. As we have seen in the article, scientific literature leans toward high frequency whenever fatigue is properly controlled and monitored.

VBT for Powerlifting: Do the Minimum Many Times a Week to Improve the Maximum in the Long Term

Despite the differing opinions from coaches and athletes on the topic, available data so far suggests that frequent high-intensity training can be beneficial in terms of strength gains (Mattocks et al., 2017). One of the reasons why high-frequency training is effective in increasing strength in weightlifters, powerlifters, and trained individuals is that it is a valid method for increasing overall training volume (Schoenfeld et al., 2015; Zourdos et al., 2015).

Furthermore, practicing the squat, bench press, and deadlift more frequently allows for greater improvement in technique, both through repetition and by being able to work on it with less fatigue in each session. The less volume we use per session, the more intensity and quality we can achieve in that volume. This, in turn, allows us to produce more average force in each repetition and achieve greater neuromuscular activation, a result obtained through high-frequency training (Hartman et al., 2007; Phillips et al., 1997).

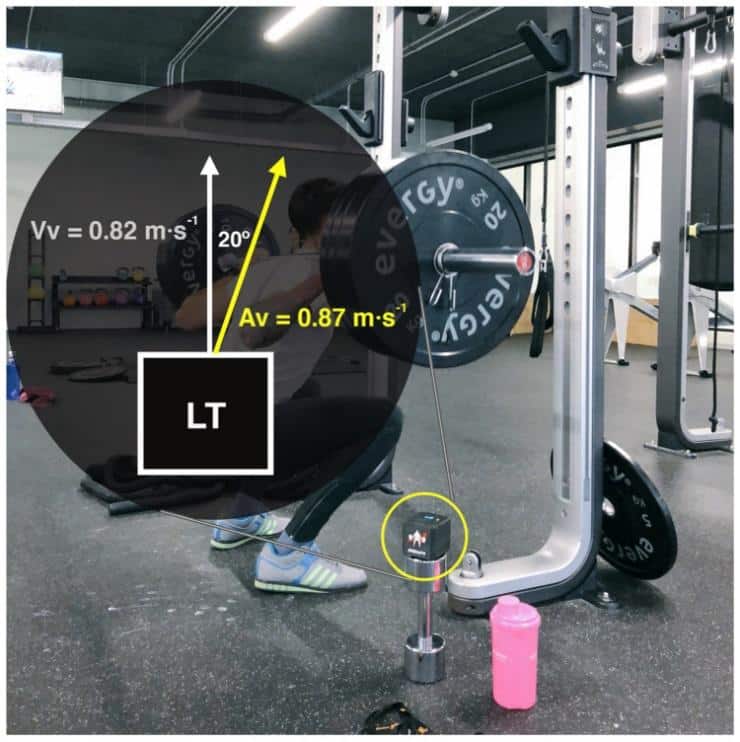

The problem arises when we incorporate high frequency into powerlifting without managing load and fatigue effectively. To prevent this, we have Velocity-Based Training (VBT), which precisely indicates the actual fatigue an athlete is experiencing with each set of training (Balsalobre-Fernández & Torres-Ronda, 2021). By controlling the bar speed in a squat, bench press, deadlift, or any exercise, we can gauge the fatigue we are generating. This is possible because we can associate the speed of each repetition with a %1RM and program fatigue based on the speed loss throughout the set.

This strategy allows for precise prescription of workouts, even training daily, seven days a week. Of course, the athlete also needs personal space and time, so additional factors need to be considered when deciding on the number of training days. Although training seven days a week is possible, even recommended with precise fatigue monitoring, there might be added psychological fatigue. Considering all these factors, we will program the number of training days per week, with fatigue per session ideally being lower the more days we train per week.

Having a velocity measurement device like Vitruve helps assess the athlete’s condition during warm-up, indicating if they are carrying over fatigue from the previous session or facing external factors like stress in their daily life, lack of sleep, etc. Throughout the session, we monitor the speed loss in each repetition, prescribing a low speed loss (e.g., 7%) if we want the session to incur minimal fatigue or a slightly higher speed loss (20% – 30%) if we train fewer days per week and can fatigue the athlete a bit more in each session (Zhang et al., 2022, 2023).

Conclusion

A decade or two ago, powerlifters followed three or four-day-per-week programs, but each day was incredibly demanding. If you have tried any of the classic powerlifting programs, you know what we are talking about. Currently, the majority of powerlifting competitors follow a high-frequency model, training about five or six times a week, mirroring disciplines such as Olympic lifting. Therefore, the true answer to “How many times a week do powerlifters train?” is “as many times as their fatigue allows.”

By training more days, we can refine the technique in squat, bench press, and deadlift, while being more rested each day by spreading the volume across more days, potentially even increasing weekly volume. The coach plays a key role in deciding how many days to train and how to structure each day. Velocity-Based Training (VBT) becomes a valuable tool for the coach, allowing them to program fatigue based on speed loss using speed measurement devices like Vitruve.

References

Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Fisher, J. P., Kolokotronis, P., Gentil, P., & Steele, J. (2018). Reduced Volume ‘Daily Max’ Training Compared to Higher Volume Periodized Training in Powerlifters Preparing for Competition—A Pilot Study. Sports, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS6030086

Balsalobre-Fernández, C., & Torres-Ronda, L. (2021). The Implementation of Velocity-Based Training Paradigm for Team Sports: Framework, Technologies, Practical Recommendations and Challenges. Sports, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS9040047

Colquhoun, R. J., Gai, C. M., Aguilar, D., Bove, D., Dolan, J., Vargas, A., Couvillion, K., Jenkins, N. D. M., & Campbell, B. I. (2018). Training volume, not frequency, indicative of maximal strength adaptations to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(5), 1207–1213. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002414

Ferland, P. M., & Comtois, A. S. (2019). Classic powerlifting performance: A systematic review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33, S194–S201. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003099

Hartman, M. J., Clark, B., Bembens, D. A., Kilgore, J. L., & Bemben, M. G. (2007). Comparisons between twice-daily and once-daily training sessions in male weight lifters. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSPP.2.2.159

Heaselgrave, S. R., Blacker, J., Smeuninx, B., McKendry, J., & Breen, L. (2019). Dose-Response Relationship of Weekly Resistance-Training Volume and Frequency on Muscular Adaptations in Trained Men. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 14(3), 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSPP.2018-0427

Helms, E. R., Storey, A., Cross, M. R., Brown, S. R., Lenetsky, S., Ramsay, H., Dillen, C., & Zourdos, M. C. (2017). RPE and Velocity Relationships for the Back Squat, Bench Press, and Deadlift in Powerlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(2), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001517

Hillerström, E., & Brandin, W. (2023). The Relationship of Training Frequency and Wilks Score in Competitive Swedish Classic Powerlifters : A Quantitative Questionnaire Study. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:gih:diva-7565

Mattocks, K. T., Buckner, S. L., Jessee, M. B., Dankel, S. J., Mouser, J. G., & Loenneke, J. P. (2017). Practicing the Test Produces Strength Equivalent to Higher Volume Training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 49(9), 1945–1954. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001300

Phillips, S. M., Tipton, K. D., Aarsland, A., Wolf, S. E., & Wolfe, R. R. (1997). Mixed muscle protein synthesis and breakdown after resistance exercise in humans. The American Journal of Physiology, 273(1 Pt 1). https://doi.org/10.1152/AJPENDO.1997.273.1.E99

Saric, J., Lisica, D., Orlic, I., Grgic, J., Krieger, J. W., Vuk, S., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2019). Resistance Training Frequencies of 3 and 6 Times Per Week Produce Similar Muscular Adaptations in Resistance-Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33 Suppl 1, S122–S129. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002909

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ratamess, N. A., Peterson, M. D., Contreras, B., & Tiryaki-Sonmez, G. (2015). Influence of Resistance Training Frequency on Muscular Adaptations in Well-Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(7), 1821–1829. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000970

Shaw, M. P., Andersen, V., Sæterbakken, A. H., Paulsen, G., Samnøy, L. E., & Solstad, T. E. J. (2022). Contemporary Training Practices of Norwegian Powerlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(9), 2544–2551. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003584

Zhang, X., Feng, S., & Li, H. (2023). The Effect of Velocity Loss on Strength Development and Related Training Efficiency: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/HEALTHCARE11030337

Zhang, X., Feng, S., Peng, R., & Li, H. (2022). The Role of Velocity-Based Training (VBT) in Enhancing Athletic Performance in Trained Individuals: A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19159252

Zourdos, M. C., Dolan, C., Quiles, J. M., Klemp, A., Blanco, R., Krahwinkel, A. J., Goldsmith, J. A., Jo, E., Loenneke, J. P., & Whitehurst, M. (2015). Efficacy of Daily One-Repetition Maximum Squat Training in Well-Trained Lifters. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(5S), 940. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000479287.40858.B7