21 de October de 2024

5 Myths & Misconceptions in Velocity-Based Training (VBT)

Velocity-Based Training (VBT) has become increasingly popular in the strength and conditioning community over the past few decades and is starting to be looked at now as a must-have training tool for serious programs.

By using velocity as a key metric, VBT offers a more individualized & data-driven approach to training than traditional methods. This unlocks the potential for greater results and more sustained training success.

However, several myths and misconceptions are still in circulation when it comes to the use of VBT. These mistakes could potentially be limiting coaches from adopting VBT, or even tampering with the effectiveness of VBT applications. Here, we debunk five common myths about VBT and showcase how you can get the most out of your VBT training.

1. Misconception: Only Programming Reps in Training

Sounds crazy right? Shouldn’t you program sets & reps for your athletes? Well, yes, but only utilizing training schemes with a set amount of volume could be leaving your athletes at a disadvantage.

Instead, you should try to incorporate velocity loss cutoffs or target velocity zones as a form of volume regulation.

A velocity loss cutoff refers to a predetermined percentage of decrement in movement velocity. This is an accurate indicator of fatigue both inter and intra set usually between 10-20 percent.

By monitoring the decline in movement velocity during a set or between sets, coaches and athletes can establish a specific point of velocity loss in which the set should be ended.

This approach helps in preventing excessive fatigue, optimizing results and ensuring that the quality of each session remains high and intentional.

Velocity Based Training 【 #1 VBT Guide in the World 】

Another option is to establish velocity zones, choosing points on which we want the speed of the lift to be in between. Vitruve offers the ability to use this in the software and you can implement it by looking for a target speed (ex. 0.68m/s) and establishing a cutoff velocity at a certain percentage below that target speed (ex. @10%VL is 0.61m/s). This method can be used to maintain a target velocity and its corresponding percentage of loss, instead of the fastest rep of the set.

Training with sets & reps is not “bad” or “wrong” but as with most VBT applications, quantifying & autoregulating with precise data will ultimately get your athletes a better result.

2. Misconception: Only Using VBT with Light Loads for “Explosiveness”

Another misconception is that VBT is only useful for training with light loads to develop explosiveness. The reality is that VBT is simply a method of quantification — it’s training & tracking.

VBT itself does not produce outcomes, it’s the application & effort put into specific programming that gets the results.

VBT can be applied to any lift, at any load, with athletes from all experience levels.

When you start to think of VBT as a training tool rather than a training program, it will shift your perspective into understanding that the data is only being collected so that coaches and athletes can analyze it and make the proper adjustments to the program.

The old saying goes, “What gets measured gets managed,” and that sums up VBT nicely. Having the data is great, but acting on that data and allowing it to influence coaching decisions is where the magic happens.

What Is An Explosive Strength Training Program Like?

3. Misconception: VBT Makes Training More Complicated

This is one of the most common myths in VBT and I feel that it stems from coaches either not understanding VBT or not putting in the effort to understand it. Quite honestly, it’s kind of a lazy excuse.

Some athletes and coaches avoid VBT, fearing it will complicate their training. While VBT does introduce additional metrics, it ultimately simplifies the decision-making process by providing real-time objective feedback.

Instead of relying on subjective measures or predetermined percentages of 1RM, VBT allows for immediate adjustments based on actual performance. This can streamline training sessions and make them more efficient.

I don’t know about you, but when I travel from point A to point B, I use GPS navigation. It tells me exactly where to go, shows me my route, gives me an estimated time of arrival, and if there’s traffic, it finds a better route.

Does anyone think GPS navigation makes traveling more complicated? NO.

This logic makes it really hard to understand how people think VBT makes training more complicated. Like GPS, VBT helps us understand our route to results and showcases the best ways to get there, notifying us of any red flags along the way. Not only that, but VBT individualizes training with two single metrics, first, establishing a velocity we already established an objective load, adapted to the ability of the individual, just like the 1RM, but with a major difference, that is a load that adjust to daily fluctuations of readiness and improvements. The second metric is the %VL, so with one single metric, such as 10% VL, we individualize volume to the fatigability of all athletes with the same relative load.

In 2024, our society is more tech savvy than ever. Introducing things like VBT actually makes training LESS complicated because it gives coaches and athletes a relatable way to understand everything that is happening during a session and within their body. We use technology for everything else in our lives to make it more simple & convenient, and the same should go for training.

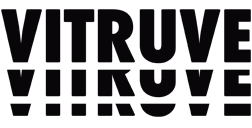

4. Misconception: Using the Same Velocity Standards for All Lifts

One of the biggest mistakes I personally made for years with VBT is using the same velocity standards, zones and goals for every lift (and every athlete).

Each exercise has unique biomechanical characteristics, resulting in varying velocity profiles. The same goes for athletes, but we’ll focus on that another day.

For instance, the 1RM velocity for a squat will differ from that of a bench press or deadlift. It’s essential to establish specific velocity benchmarks for each lift to accurately assess and optimize performance.

In general — for a Back Squat, 1RM typically occurs around .32 m/s. For a Bench Press, that 1RM is more around .18 m/s. For a Deadlift, that 1RM drops to an even lower .14 m/s.

One helpful way to create your own standards for both lifts & athletes is to have them perform a load-velocity profile for all of your KPI lifts.

Load-velocity profiling refers to the systematic assessment of an athlete’s performance across various loads in a given lift. This process aims to establish personalized profiles that showcase the unique force production characteristics of each individual.

Essentially, load-velocity profiling allows us to learn more about how an athlete’s strength output varies in response to different loads and movement velocities in various lifts.

The concept of load-velocity profiling is rooted in the understanding that an athlete’s performance is not static but rather dynamic and multifaceted.

By evaluating an athlete’s ability to generate force at varying loads, we gain valuable insights into their strength-speed profile.

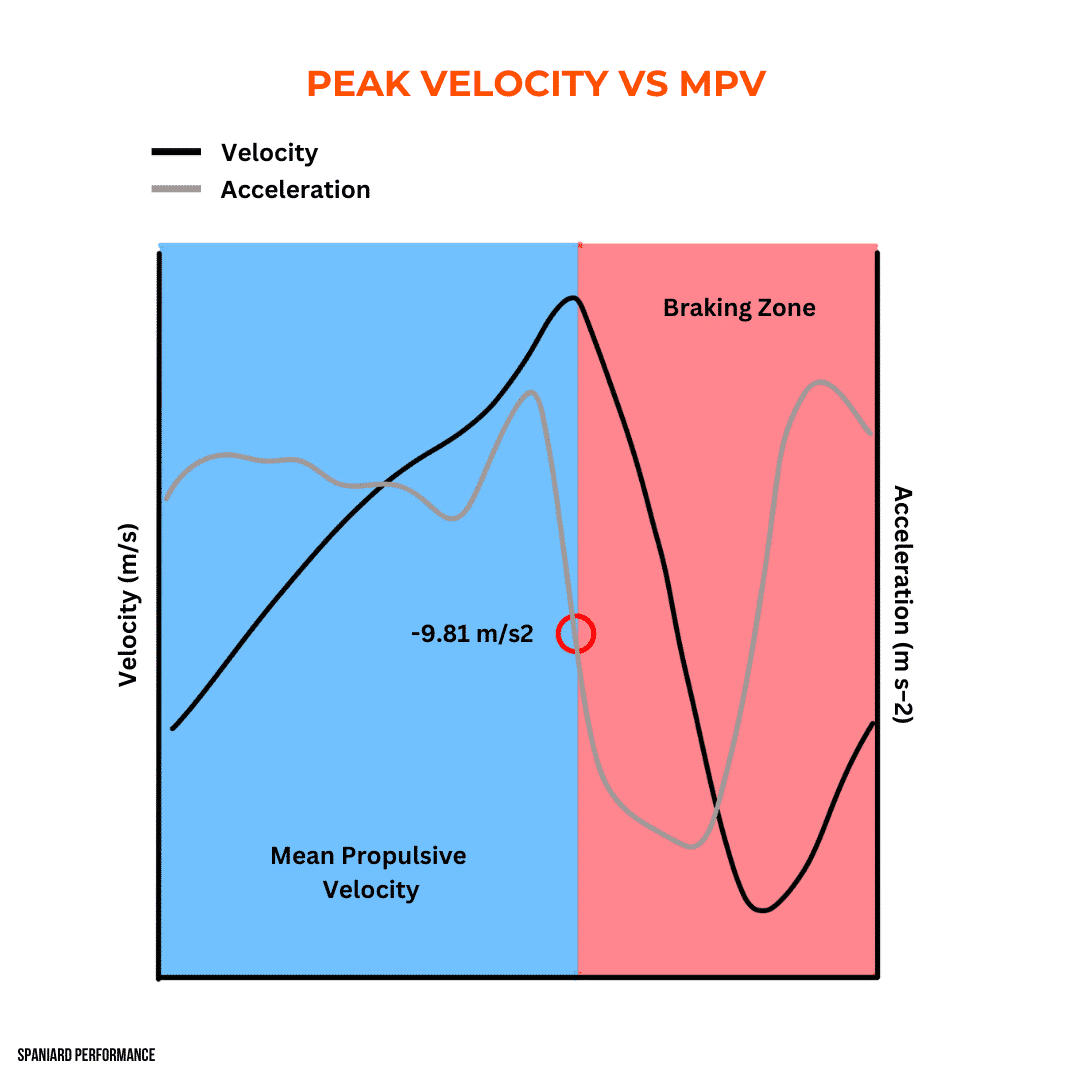

5. Misconception: MV, MPV and PV are all the same, right?

Understanding the distinction between Mean Velocity (MV), Mean Propulsive Velocity (MPV), and Peak Velocity (PV) is crucial for effective VBT work.

Mean Velocity (MV) is the average velocity across the entire concentric phase. MV is useful for assessing overall and broad movement velocity, and can be utilized to determine the intensity of the exercise relative to an individual’s capabilities.

Mean Propulsive Velocity (MPV) is the average velocity from the start of the concentric phase until the acceleration is less than gravity (-9.81 m/s²), also known as the propulsive phase. MPV excludes the deceleration phase or any floating phase, which occurs after the peak force has been exerted.

Peak Velocity (PV) refers to the maximum instantaneous velocity value reached during the concentric phase of a lift. This represents the athlete’s absolute capabilities better than MPV or MV in some cases and only considers the exact moment in which that peak was reached.

Blending these metrics can lead to confusion and misinterpretation of data. Utilizing each velocity type appropriately provides a clearer picture of an athlete’s performance and areas for improvement.

For example, ballistic movements such as Olympic lifts are best measured in Peak Velocity, while traditional lifts such as a Back Squat would be best measured in MPV or MV.

Both MV and MPV are valid & reliable metrics, however, they are slightly different which could lead coaches to favor one or the other based on their environment, athlete population and goals in training.

The main difference between MPV and MV is that MPV only captures the average velocity of the portion of the movement where the lifter is actively propelling the resistance upward.

In practical terms, MPV is often considered a more relevant metric as it only reflects the speed at which force is being effectively applied to move the resistance against gravity.

And, while PV may offer a more reliable interpretation of an athlete’s maximal outputs, MPV gives a more comprehensive linear trend when constructing load-velocity profiles and other load estimations.

Vitruve users will always have access to MV, MPV and PV values. But when in doubt, we recommend using MPV for all non-ballistic movements and using PV for all ballistic movements.As you can see, there are misconceptions that can lead coaches to either push back on the use of velocity based training, or to use it incorrectly, which will lead to a lack of understanding of why VBT can be so valuable.

Understanding these concepts will change your perspective on velocity based training completely.