Today, despite the amount of information that we can find in books, courses, platforms or the internet in general, the vast majority of people do not have enough bases to develop by themselves a nutritional scheme to follow that is healthy, nutritious and according to their needs. In fact, for that there are nutrition professionals (Dietitians and Dietitians-Nutritionists) whose work is increasingly important within society due to the considerable increase in obesity in recent years and the worsening of health in general. Recently the ENPE study (1) has come to light where the authors conclude that more than 53% of the Spanish population suffers from obesity or overweight. To say that the sample was 6800 subjects from all over Spain and anthropometric tests were carried out, in addition to questionnaires of consumption and life habits.

On the other hand, athletes or sportsmen, both recreational and professional, are more aware of the importance of a correct diet in their day to day. Although the objective in this profile of subjects is more aimed at improving their discipline, we can say that, indirectly, the vast majority will achieve a better state of health by the mere fact of wanting to improve in their activity; because as we well know, physical activity is health. Of course, this statement has several nuances since in elite sport: performance > health and in the long run many professionals end up with problems of various kinds due to low percentages of body fat (very problematic especially in women), restrictive diets or problems associated with this type of diets (TCA, alterations of lipid metabolism and glucose, alterations of the cardiovascular system, etc.) and also by very high calorie diets together with a high fat percentage due to the characteristics of some sports (strongman or discus throw among others). Despite all this, it seems that elite athletes have around 5 years more life expectancy than the general population (1).

While we will not be able to give a magic recipe that serves for any athlete, we can guide and give some recommendations that can be used as a guide and serve as a reference from which you can make adjustments to improve your current dietary pattern.

Calories

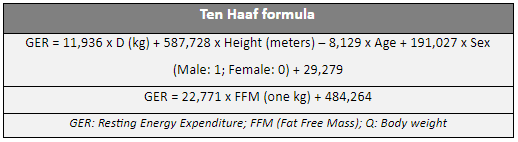

To calculate our TEE (Total Energy Expenditure), first, we must make use of different predictive equations that help us calculate our theoretical BMR (Basal Metabolic Rate). We can also do it by trial and error by performing a Dietary Record of 14 days calculating the food we eat, make an average based on these 14 days and adjust based on it. But for practicality and time saving we recommend using a formula and adjusting if necessary.

Because in the article we talk mainly about athletes, we will use the formula of ten Haaf,since it is a formula studied with an athlete population that performed different sports (2), although we can opt for Cunningham, De Lorenzo, Tinsley or the best known Harris-Benedict. Each formula has its pros and cons.

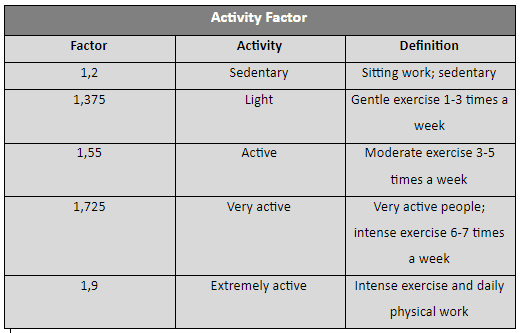

Once the data is obtained, we must know our AF (Activity Factor), which is nothing more than a multiplier that varies depending on our daily activity.

To say that the AF is an estimate so, to spin finer, we have the Metabolic Equivalence Tables or MET’s that calculate the kcal / minute depending on the type of activity you perform and the time spent. For simplicity we will not delve into it.

From here we only have to start planning our goals.

Define objectives

Within a dietary plan focused on an athlete we can differentiate between 3 types of objectives:

1. Deficit

Nutritional status where energy intake is lower than the body’s needs to maintain current weight. Broadly speaking, it is what we know as “eating less” with the aim of losing weight. Although the CICO theory (Calories In-Calories Out, that is, Calories that enter for the Calories that leave) in its most orthodox vision is fulfilled due to the first law of Thermodynamics, we must understand that energy metabolism does not work the same in all people (nor in their different contexts) nor do all foods work as simple units of energy.

In this period of fat loss, our main mission will be to avoid losing as much muscle mass as we can. Therefore, the caloric deficit must be present, but at a level that is sustainable for the athlete. We know that LEA (Low Energy Availability) is the main problem when our goal is fat loss. And it is that a very drastic cut in calories and sustained over time can produce different hormonal problems, loss of muscle mass and a negative impact on training. For example, in this narrative review (3) we see how the caloric total is the greatest determinant when it comes to losing fat mass. It is observed that a severe restriction will lead to greater weight loss as a result of carrying a greater amount of fat-free mass, which will mean a greater risk of loss of muscle mass that, as we can predict, will have a negative impact on performance.

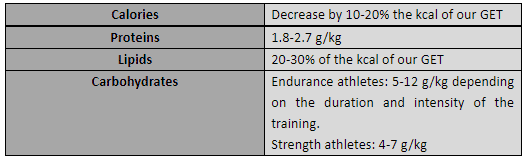

Prudently, our goal would be to reduce the kcal of our GET by 10-20% to start the deficit.

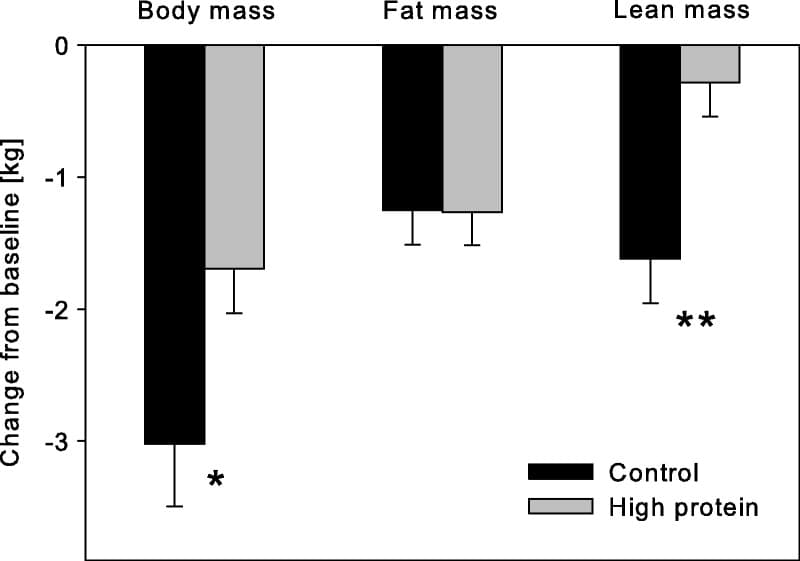

As for protein intake, we are interested in keeping it quite high to obtain a positive nitrogen balance, that is, consuming enough protein to avoid an exacerbated catabolic state. In the study by Mettler et al (4), with a group of 20 healthy athletes, they found how 2.3 g/kg of protein was higher than 1 g/kg for the maintenance of lean mass in a period of severe caloric restriction.

In this review (5) the authors conclude that a range of 2.3-3.1 g/kg of fat-free mass is a safe range to preserve as much muscle mass as possible in a period of fat loss in athletes.

That is, moving in an intake of between 1.8-2.7 g / kg of protein per day is within the current recommendations.

Regarding fat, it seems a better option in athletes to reduce their consumption and prioritize carbohydrate to avoid a drop in performance in periods of fat loss.

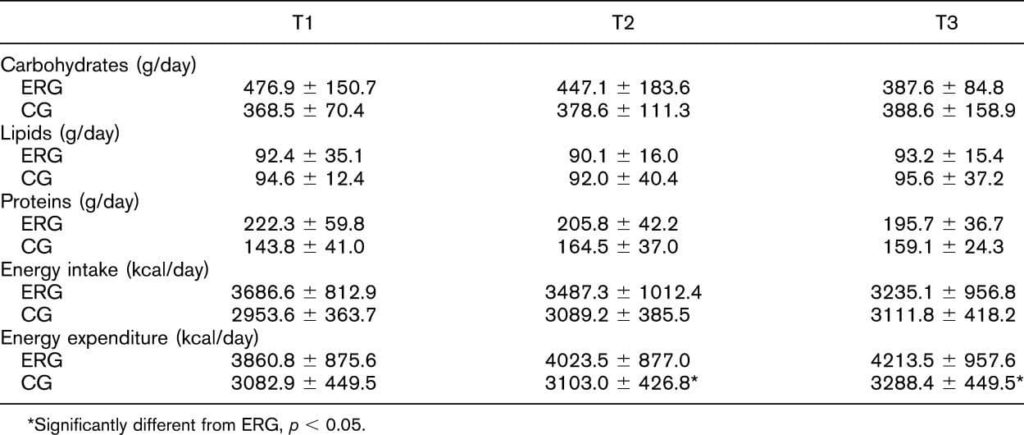

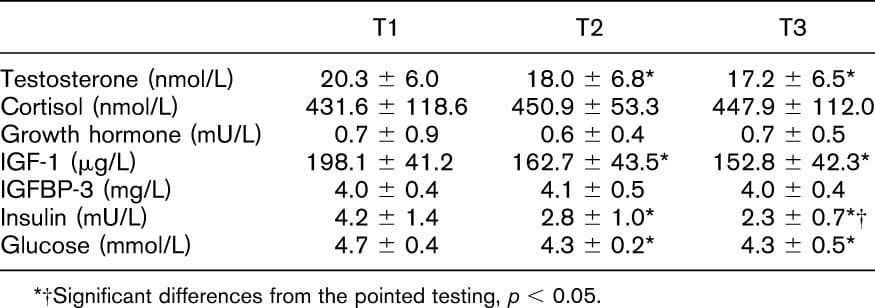

A typical belief of low-fat diets is that it negatively affects hormonal parameters such as testosterone, IGF-1, cortisol, etc. But we have studies in bodybuilders (6) where, despite consuming approximately 25% of the energy in the form of fat (close to 1.2 g / kg of body weight per day), after 11 weeks of caloric restriction the hormonal parameters studied were also affected.

In other words, the energy deficit seems to be the protagonist of the changes that occurred in the biochemistry of the subjects and not the amount of dietary fat ingested.

However, there are several studies in women athletes like this (7) that relate a low intake of dietary fat with an increased risk of injury.

As a precaution and due to the importance of fatty acids in the diet, among other things, due to the availability of fat-soluble vitamins, the goal of lipid intake should be around 20-30% of the daily caloric total.

On the other hand, carbohydrates are the best asset when it comes to maintaining performance in stages of fat loss, prioritizing them over fat intake (3), keeping them as high as we can. In endurance athletes we can move in the range of 5-7 g / kg on days of short training and light-moderate intensity; and 7-12 g / kg on training days greater than one hour of duration and with moderate-high intensity (8). As for strength athletes, moving in the range of 4-7 g/kg can be a good guide according to the authors(9).

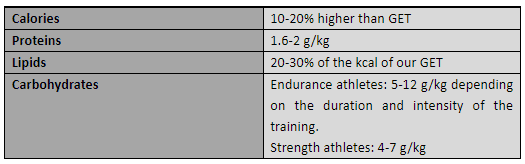

Summary of recommendations

2. Maintenance

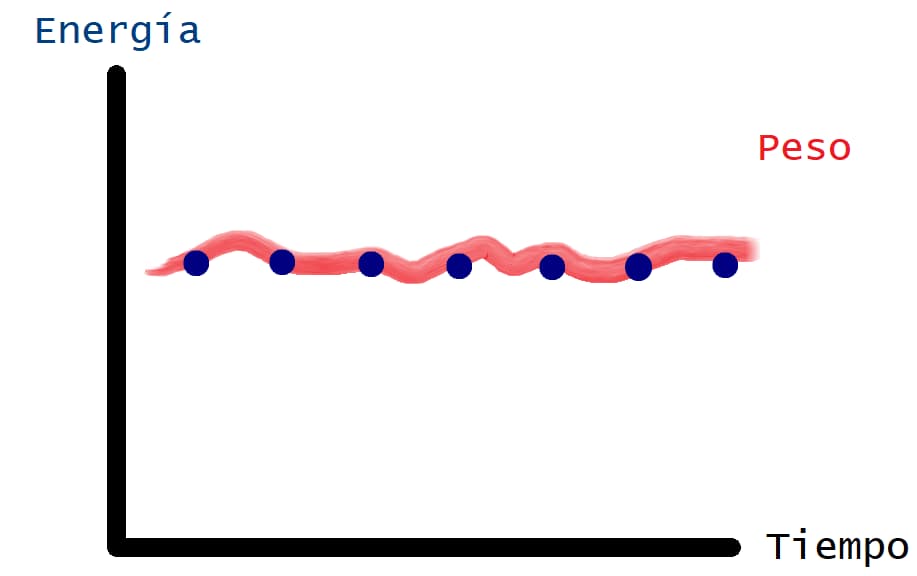

Stage where we will focus on prioritizing a nutritional state with a sufficient intake of energy that allows us not to gain weight / body fat and perform what is necessary in training. Body weight fluctuates throughout the days and even intraday due to: hydration, digestive bolus (food we have ingested), stress, hours of sleep, training, use of some drugs, alcohol intake, thermoregulation (sweating), gastric and urinary emptying (feces and urine) … We can get an idea that body weight is not a static unit.

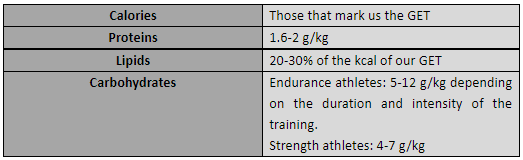

At this stage the recommendations that we can give are quite similar to those of the previous section. We will ingest the calories prescribed by the GET and reduce the contribution of proteins since we will be in a less catabolic environment than in the stage of energy deficit:

3. Surplus

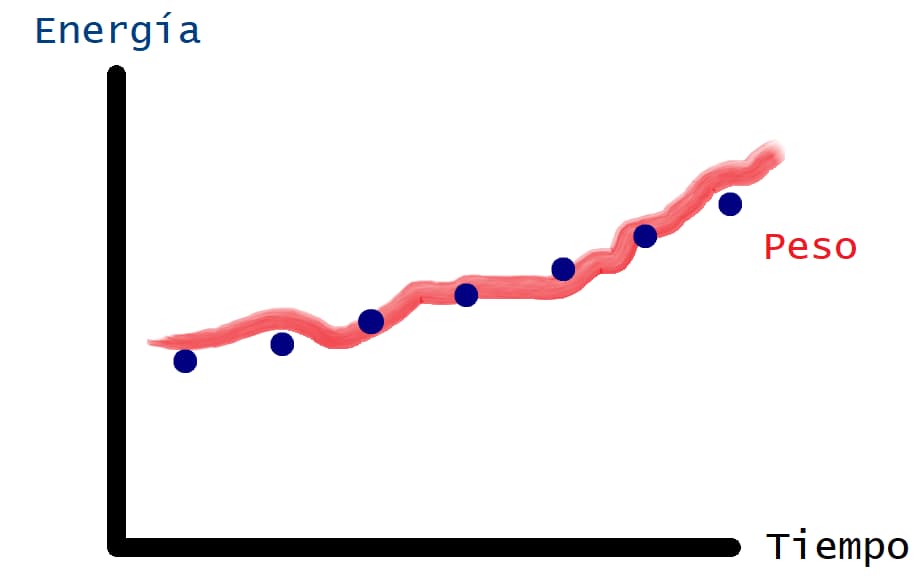

The objective in this case is to achieve an increase in body weight by gaining muscle mass, although it may also be an objective to reverse certain parameters altered by a very prolonged stage of caloric deficit or by being in a very low-fat percentage due to competition needs.

Our priority would be to achieve a good caloric partitioning throughout the day so we must be strategic with the different intakes, always considering that not all weight will be in fat-free form.

In this period, our energy needs are covered and therefore it is a good time to seek maximum performance by training and maximize the volume of work.

As you can see below, the recommendations regarding the Maintenance stage do not differ much.

Meal distribution

As a general recommendation, we will look for a more or less equitable distribution of protein throughout the day to take advantage not only of the greater satiety it gives us, but to have a greater muscle protein synthesis that benefits us when it comes to maintaining or gaining muscle mass according to the objective of the diet. A safe range would be around 0.4-0.55 g/kg per meal divided into 4 daily intakes, paying special attention to post-workout food.

Regarding carbohydrates, the ideal is to use a large part in peri-training (the time before training, during and after training) to ensure a good energy intake. And the fats can be distributed in the different meals trying to separate them from the peri-workout.

To help us with the distribution and distribution of meals, there are very useful tools available to everyone such as food trackers. We have apps like Myfitnesspal, Fatsecret, Yazio…

Conclusions

The recommendations presented here are of a general nature so, as always, we must individualize and adjust according to our needs and requirements.

It is legitimate to think that with the information we have today in the networks we can develop our own nutritional plan without much difficulty. But not everyone has the capacity and organization necessary to have strict control over food, nor does it know when to rule if a period of fat loss is required or the opposite, if you have intolerances and / or allergies, solve digestive problems of unknown origin, nutritional deficiencies due to lack of micronutrients … For this, the figure of the professional is indispensable at this point. Dietitians and dietitians-nutritionists are the professionals who can help you from the most basic as learning the different food groups, to how to enhance your diet to have a maximum performance in a sports event. Food is not only macronutrients nor is it divided into deficit, maintenance and surplus. It is a set of habits that is influenced by the environment, experiences, social and family relationships… where professionals can help you manage them in your favor to achieve your goals.

If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask! Leave a comment or contact us here.

Bibliography

- (1) Juliana Antero y col. (2020). Female and male US Olympic athletes live 5 years longer than their general population counterparts: a study of 8124 former US Olympians.

- (2) ten Haaf, Twan; J. M. Weijs, Peter (2014). Resting Energy Expenditure Prediction in Recreational Athletes of 18–35 Years: Confirmation of Cunningham Equation and an Improved Weight-Based Alternative.

- (3) Eric R. Helms, Alan A. Aragon, Peter J. Fitschen (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation.

- (4) Samuel Mettler, Nigel Mitchell, Kevin D. Tipton (2010). Increased Protein Intake Reduces Lean Body Mass Loss during Weight Loss in Athletes.

- (5) Eric R Helms, Caryn Zinn, David S Rowlands, Scott R Brown (2013). A systematic review of dietary protein during caloric restriction in resistance trained lean athletes: a case for higher intakes.

- (6) Mäestu, Jarek; Eliakim, Alon; Jürimäe, Jaak; Valter, Ivo; Jürimäe, Toivo (2010). Anabolic and Catabolic Hormones and Energy Balance of the Male Bodybuilders During the Preparation for the Competition.

- (7) Gerlach y col. (2008) Fat intake and injury in female runners.

- (8) Burke, L. M. (2010). Fueling strategies to optimize performance: training high or training low?

- (9) Slater, Gary; M. Phillips, Stuart (2011). Nutrition guidelines for strength sports: Sprinting, weightlifting, throwing events, and bodybuilding.